This past week, I’ve been thinking a lot about perfection, and its much more human counterpart, imperfection.

My first stimulus was reaching a long-awaited milestone in my daily Wordle play. I am now at the point where I can afford to lose another game and still have my reported “Win %” remain at 100%. It’s freeing to know that I have that “free game” in my back pocket along with my house key. Will I change my strategy and start with a word like “zaxes”? No. But, still…

My quest for imperfect perfection at Wordle began last September. After losing a couple of games when I first started playing, I watched my “Win %” slowly climb back toward 100%, until it reached its taunting asymptote at 99%. Then after a bit more than a year of daily play, as summer turned to fall, it happened, my “Win %” reached 100% – apparently Bumbles bounce and Wordle rounds. I have to admit it was a heady feeling to look up at the screen that morning and see perfection staring back at me – a feeling that I didn’t (and don’t) want to relinquish.

My second stimulus came from a much different source, a late-night viewing of the 2016 film Jackie – centered around Jacqueline Kennedy’s famous Camelot interview with Theodore White a week after the assassination of JFK. About an hour into the movie, Natalie Portman, as Jackie Kennedy, says of JFK’s imperfection:

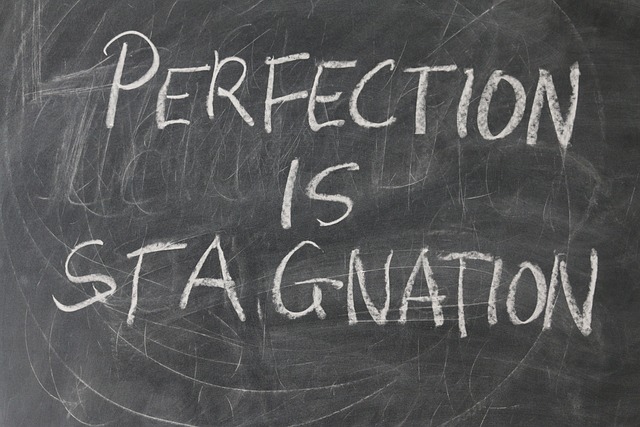

Perfect people can’t change. Jack was always getting better, stronger.

What a powerful notion, perfection breeds complacency. Growth requires acceptance of one’s imperfection, the feeling that we could do better, be better.

[I attribute the line to character because I was unable to find it while reviewing White’s 1963 Life magazine article (sitting on my bookcase) or a digital copy of his notes from the interview. I’ll keep looking.]

As is often the case, my early morning and late night encounters with perfection and imperfection bled into my midafternoon walks while listening to Carole King’s masterpiece Tapestry – perfect background for pondering life’s imperfections.

Enemy of the Good

On one walk, I mused upon how willing so many folks in our field have been to fall back on the aphorism, “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” Sound advice when applied appropriately and judiciously to counter analysis paralysis. Much more dangerous, however, when it becomes a slogan, mantra, or worse yet, a guiding principle for a field beset by complex problems (wicked problems, if you will), tight deadlines, and in dire need of innovative thinking that produces innovative solutions.

Accepting imperfection as a necessary step toward perfection – no matter how elusive – is a much different mindset than going into a problem situation expecting imperfection.

The assessment system that we develop today might look the same in either case.

The assessment system that we develop tomorrow most certainly will not.

Past Imperfect

Another day, I reflected on the collective struggles that we are having with our nation’s past. Imperfect people? Of course they were imperfect. We all are. But after accomplishing through war something that had never been done before, they set out to craft a Constitution that would peacefully establish a country and form a more perfect union of the independent colonies that country comprised. They acknowledged imperfection, but they strove to make the new country more perfect.

Seven decades later, the country had grown from 13 to 33 states, a Civil War had been fought, and that Constitution had been amended to abolish slavery (13), establish citizenship rights and equal protection under the law (14), and to ensure that the right of citizens to vote would not be denied or abridge on account of race (15).

Perfection? Not even close, but more perfect.

It has now been seven decades since Brown v. Board of Education. How do our accomplishments and advances in education during those 70 years compare to those our imperfect ancestors accomplished in the same amount of time? Some advances, sure; but certainly not enough, certainly not seven decades worth.

And the Constitution? Our last three amendments dealt with who’s in charge while the president gets a colonoscopy (25), granting the right to vote to a group of citizens we don’t trust to purchase alcohol and tobacco and to whom we won’t rent a car(26), and making it a little more difficult for members of Congress to raise their own salaries (27).

Sure, the country’s original foundation was sandy, but it’s been fortified enough to sustain the glass houses and houses of cards we’ve built upon it. It’s a choice whether to acknowledge imperfection and to continue to fortify it or to raze it to the ground in search of some yet to be defined perfection.

In education, we may never get to 100% Proficient or reach long-term ESSA goals or agree on what books should be in school libraries, but can’t we make public education a little more perfect.

Imperfect Measures

On my next walk, I ruminated on our imperfect field. Not on the issues about reconciling our own past with our present and future, but rather on our ongoing struggles to deal with perfection.

Our theoretical framework and vast statistical machinery collapse when a student earns a perfect score on a test (perfectly correct or perfectly incorrect).

We cannot even seem to acknowledge, let alone communicate to test users, the differences in the precision of a perfect score when considered in terms of a student’s true score and their observed score. Only one of those is of practical importance to educators. Hint: It’s not the one that seems to be important to us.

I recalled with bemusement the struggles over how much imperfection could be present in a student’s response to a constructed-response item or writing prompt before that response no longer qualified to receive a perfect score. I can only imagine that those debates will increase in complexity (and fervor) as the tasks that we assign to students and the responses we expect of them increase in complexity.

Which led me to meditate on one of the most vexing scoring problems we face year after year:

How do we maintain the standard for a “perfect score” when student performance is improving over time?

It has never been easy to convince scorers that a student response deemed worthy of a perfect score in Year 1 of an assessment program still deserves to receive a perfect score in Year 3, 4, or 5 when there are now so many examples of better responses. We have done a pretty good job holding the fort on equating items, but I’m sure that the standard for a perfect score has drifted on new items – and I’m really not sure what the downstream effect of that drifting is on test results. But that’s a question for another day.

Where my mind went on that walk, was whether it will become more or less difficult to maintain a scoring standard across years when scoring is handed over to AI. I’m talking about real artificial intelligence that is left to “learn” on its own, not simply automated scoring based on an algorithm with clearly defined indicators that we can control.

What do we do when the AI engine decides that the response that received a score or ‘4’ last year ain’t a ‘4’ no more?

Will our tapestry unravel when we pull on that thread?

Or will we finally realize that in order to be useful to educators we have to become comfortable living in the imperfect world of observed scores?

Our measures will always be imperfect, but less imperfect than the decisions that imperfect people will make without them.

We have to strive to make them more perfect, knowing that process has to be imperfect.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay