Core

- a central and often foundational part usually distinct from the enveloping part by a difference in nature

- a basic, essential, or enduring part

Education Reform, in general, and test-based education reform since NCLB, in particular, has not been kind to the core of public education; that is, to the core values, beliefs, and ideals that define the purpose of, shape the form of, and guide the direction of public education in the United States.

From the beginning, the broad strokes of that core have been clear. As John Adams wrote to his young son, John Quincy in 1781, “you will ever remember that all the end of study is to make you a good man and a useful citizen.” For as he had written in 1765, “liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people, who have a right…and a desire to know…” Produce (for lack of a better word) productive, useful, engaged citizens who have a desire to know and to learn, that is the purpose of public education.

To be fair, at the moment, the nation as a whole seems just a tad unsure of what makes one a good person and a useful citizen, as opposed say to a useful idiot. There is disagreement and confusion over what some of those core values and beliefs are or should be. The country’s current state of confusion over who we are, who we were, and who we want to be, self-reflection with a heavy dose of reckoning, however, only increases the urgency for public education in the United States to fulfill its most central and enduring function, which is, as it ever was, to produce citizens able to understand, consider, and engage in productive debate about those very questions.

The question, therefore, that has been running through my mind these past few weeks is how did we, as a country, as educators, as assessment specialists, allow ourselves to lose sight of the core in favor of an infantile obsession over the minutiae of English and mathematics test scores.

Why have we fiddled and diddled with figuring out new ways to package and report the same two test scores (Look Ma, I’m an accountability index!) while allowing the fire within our students to burn out?

We Didn’t Start Out This Way

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, there was healthy debate about what values and beliefs should be part of the core (see William Bennett), but the core was still front and center.

In 1994, Massachusetts, for example, published the Massachusetts Common Core of Learning which “sets forth the broad goals for education identifying what students should know and be able to do. The goals reflect what citizens highly value and see as essential for success in our democratic society.”

It’s critical to note that the Commonwealth clearly understood that answering that question was a prerequisite to the key steps that followed:

- Developing Curriculum Frameworks (aka state content standards)

- Implementing a State Assessment Program

Each of the three elements (core, standards, assessment) were interrelated and indispensable, of course, but there is a natural sequence or ordering. You cannot decide what to include in curriculum and instruction until you’re clear on the big picture, WHY you’re doing this in the first place. You cannot assess how well you are doing until you understand and can clearly describe what you are doing.

That ordering was reflected in the Massachusetts timeline during the 1990s:

1993: Massachusetts Education Reform Act

1994: Massachusetts Common Core of Learning

1996: First Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks

1998: First Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) administration

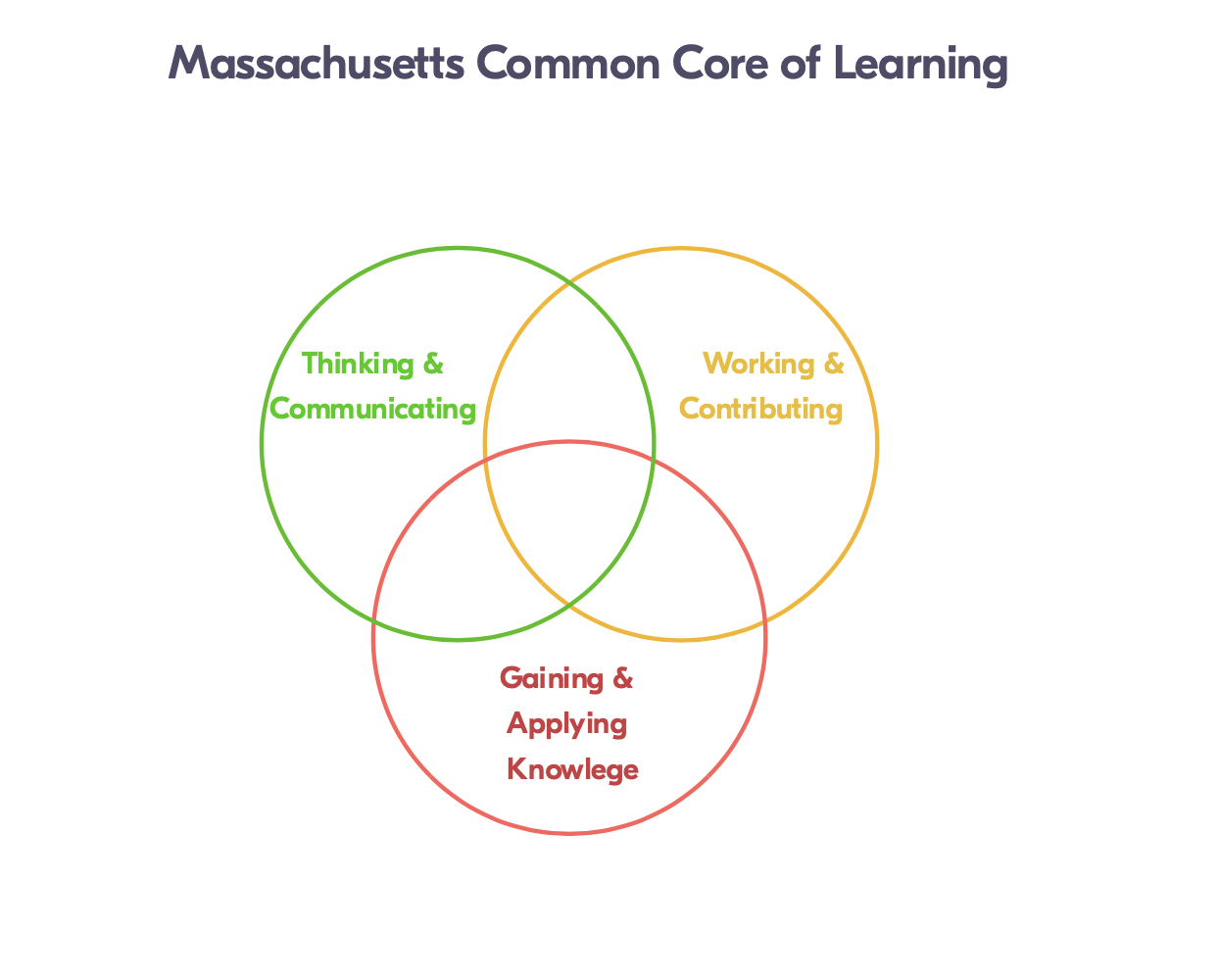

A two-page summary, “What is the Purpose of the Common Core of Learning?” depicts the three principal components of the core, Thinking & Communicating, Working & Contributing, Gaining & Applying Knowledge, as interlocked rings:

It’s tempting to interpret the image of the common core as a Venn Diagram and jump right in, searching for curricular overlaps and assessment intersections, but I think that a more appropriate starting point is to view the image as similar to the Olympic rings: three interconnected concepts coming together to form the whole; in this case the whole student, the useful and productive citizen.

Thinking & Communicating included read, writing and communicate effectively, using the arts, mathematics, computers and other technologies effectively, and defining, analyze and solve complex problems.

Working & Contributing described the importance of being able to study and work effectively, and to demonstrate personal, social, and civic responsibility.

Gaining & Applying Knowledge identified the areas in which students should be able to acquire, integrate and apply essential knowledge: literature and languages (yes, plural languages); mathematics, science & technology; social studies, history & geography; visual & performing arts; and health – including an emphasis on personal growth, fitness, and enjoyment.

Throughout there was a focus on engagement and lifelong learning.

Finally, the document laid out a set of shared responsibilities for students, families and schools, schools, schools and communities, communities and the Commonwealth.

It was a bold vision and a comprehensive blueprint.

But again, it was not a particularly new vision. It was simply updating for the 21st century the concept of what it would mean and require to be a good person and a useful citizen.

Where, How, and Why Did We Go Wrong?

There are obviously larger societal, social, and political forces that contributed to leading us to where we are today, but for now let’s focus on the system of schools and tests.

The short answer to where we went wrong: Accountability.

The slightly longer answer: Accountability tied to Title I.

Title I was never about the entire core. It was about reading and mathematics.

You can make the argument, as many have, that basic skills/proficiency in English language arts and mathematics are a prerequisite to success in everything else; and states and schools should certainly be held accountable for the allocation of Title 1 funds. But “SCHOOL ACCOUNTABILITY” never should have been limited to Title 1. (And Title 1 accountability should not be expanded to something that it is not.)

Next in line behind accountability was the focus on knowledge and skills in individual content areas devoid of consideration of the larger goal. There may be advantages to a more interdisciplinary approach to organizing curriculum and instruction, but for time immemorial (that is, at least as long as I have been alive), the content of courses in English, languages (including Latin), social sciences, and even the natural sciences were geared around conveying and reinforcing a social narrative, around producing good people and useful citizens. Mathematics courses not so much, but as a country, we’ve kind of sucked at figuring out why we are teaching mathematics.

The recent intense focus on breaking content areas down to identifiable skills, individual standards which could be taught, mastered, and assessed, detracted from the bigger vision. Content areas, like Humpty Dumpty, are nearly impossible to put back together again after they’ve been broken down into a million tiny pieces.

Then there are the state tests. NCLB and Title I Accountability are a big reason, but not the only reason, why states stopped developing or never attempted to develop tests in all of those other content areas. Yes, there were once states with state tests in the arts, humanities, and health. And even History – ah yes, whose history.

We simultaneously expected too much and not enough from state-supported assessment. On the one hand, from state tests being a “dipstick” or “thermometer” signaling a potential problem at the school- and, with less certainty, student-level, we wanted comprehensive diagnostics with recommended treatments. On the other hand, after getting burned dipping our toes in the water in the 1990s (I love mixed metaphors), we ran and hid from the prospect of integrating state-supported assessment into schools.

Let them have multiple-choice items!

Finally, we botched the Common Core State Standards by mislabeling it the common core when it could never be more than a set of English and mathematics content standards, albeit a very good set of content standards.

Where Do We Go From Here?

We do things in the right order.

We don’t start with the tests.

We don’t start with competencies or content standards or whatever other term might become popular tomorrow.

We journey back to the core.

As uncomfortable and difficult as it may be, we tackle the difficult questions of what it means to be a good person and useful citizen in the United States in the 21st century, acknowledging that probably requires being a useful global citizen as well.

We will disagree on a lot of things about the essential components of being a good person and useful citizen, some important, many not so much; and there will certainly be disagreement about how to shape the narrative. I am confident, however, that there is sufficient common ground to establish a common core.

Will we get everything right the first time? Of course not. Will we have to agree to disagree and to table some issues for the time being because they are too hot to handle in the current climate. Probably. But that’s OK. As much as I hate the saying and the way it has been used in education, we cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

There is no other way, no easy way.

We have to respect the process.

We have to respect each other.

We have to respect the common core.

Header image by Iryna Rodríguez from Pixabay

You must be logged in to post a comment.