After more than a quarter century, the teachers’ union in Massachusetts finally achieved victory in their war on the use of the state’s Grade 10 MCAS test as a high school graduation requirement. Where legal actions and legislative lobbying had failed, a referendum question replete with all of the characteristics that a Populist appeal must contain succeeded. Power to the people!

The pressing question to the teachers’ union, as posed by the King George character in Hamilton is, You’ve been freed. What comes next?

Before addressing that question, however, allow me to be a bit nostalgic. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I was part of the cross-unit team at the Massachusetts DOE, led masterfully by Commissioner Dave Driscoll, charged with implementing the tests and test-based graduation requirement mandated by the landmark Massachusetts Education Reform Law of 1993.

Between A Rock and a Hard Place Facing A Wicked Problem

It’s never easy when you try to use the same test and test scores for both school and student accountability; throw teacher accountability into the mix (formally or informally) and you complete an unholy trinity. Critics of high-stakes for students point out the injustice of holding students accountable for the shortcomings of the school or for the failure of the state to adequately support its schools. The other side of the coin is the injustice in handing a diploma to students and sending them out into the cruel world lacking what the state has determined to be fundamental knowledge and skills in reading, mathematics, and science. Advocates for students with disabilities and English learners perhaps best reflected this dilemma, supporting the inclusion of all students to ensure that they receive appropriate instruction and services, but struggling with how that should play out with regard to graduation requirements for individual students.

There is neither an easy nor perfect solution.

Striking a Balance To Meet the Letter of the Law and the Spirit of Reform

Armed with the resolve to get it right, the fear of getting it wrong, and the AERA position statement on high-stakes testing, we set out to establish an MCAS graduation requirement that was more standards-based than test-based; one that was not solely based on the test; that is, a requirement that would allow the Commissioner to truthfully claim that no student who possessed the requisite knowledge and skills would be denied a diploma because they could not pass the test.

And of course, that requirement also had to be technically sound and legally defensible – because there would be lawsuits.

First question, where to set the bar?

The state’s goal, later solidified by NCLB, was that all students would be Proficient or higher on the tenth grade standards (Level 3 out of four: Failing, Needs Improvement, Proficient, Advanced), but we wanted to leave room because false negatives were a far greater concern than false positives. The state also wanted to provide time for schools to ramp up their implementation of the standards.

Rather than trying to establish a new achievement level cutscore just for graduation, we decided to go down a full achievement level and set the so-called passing score at Level 2 (Needs Improvement). Statistically, there was little chance of a Proficient student performing at Level 1 by chance; and as the Commissioner noted at the time, the work of students at Level 1 spoke for itself and it didn’t say here was a student who had the knowledge and skills needed for graduation.

Multiple Opportunities

Common sense, fairness, and the AERA position statement called for students to be provided multiple opportunities to meet the requirement. The law called for the graduation requirement to be based on student performance on the tenth grade test. In the early years of the program, students had up to 5 additional opportunities to take the test prior to their scheduled graduation. Again, statistically it was extremely unlikely that a student with the knowledge and skills to perform at Level 2 would fail to achieve the passing score three times, let alone students who were actually Proficient. But what if they did?

Performance Appeal

What if for some reason there was a particular student who was unable to demonstrate their actual level of knowledge and skills through the test after taking it multiple times?

We created a performance appeal process through which student performance in their coursework would serve as a portfolio to demonstrate that they had the knowledge and skills necessary to meet the Level 2 standard. If the district could document that other students performing in the same sequence of courses and receiving similar grades tended to pass the test, then the student would be deemed to have met the graduation requirement. (If none, or few, students in the district taking that sequence of courses and receiving similar grades were able to pass the test that signaled a systemic problem in alignment of expectations and not an individual test-taker problem.)

Ultimately the ball was in the educators’ court and in their hands – right where they wanted it.

Raising The Bar

After I had moved on from the department, when it came time to raise the bar to Proficient, the department and Board of Education placed that responsibility in the hands of local educators. For each student scoring below Proficient, but above the passing score, the district had to develop an educational proficiency plan (EPP) to show the student, parents, and state how the district was going to attempt to move the student toward proficiency over the eleventh and twelfth grade. As described by the department, each EPP includes, at a minimum:

- a review of the student’s strengths and weaknesses, based on MCAS and other assessment results, coursework, grades, and teacher input

- the courses the student will be required to take and successfully complete in grades 11 and 12

- a description of the assessments the school will administer on a regular basis to determine whether the student is moving toward proficiency.

Districts could use the MCAS test to assess student proficiency in grades 11 or 12, but there was no state requirement that they do so, and no state requirement that the student had to achieve a particular score on any standardized test.

That is the process that has been in place over the past 15 years or so, the one that was maintained by a broad-based review committee that invited everyone to the table at the beginning of 2020 just prior to the pandemic, and the policy that the teachers’ union opposed, and that voters rejected. (Note that the teachers’ union chose to stand at the back of the room rather than take a seat at the table in 2020.)

So, if the test-based graduation requirement wasn’t actually a test-based graduation requirement, what is it that has really gotten teachers so riled up for all this time?

The answer to that question is the same today as it was back in the 1990s when all of this started.

It’s The Standards, Stupid

(At the time we were designing the MCAS graduation requirement and adapted this mantra, Bill Clinton was president and we were not far removed from his advisor James Carville’s admonition on which the heading to this section is based.)

MCAS-based graduation requirement or no MCAS-based graduation requirement (even with or without MCAS at all), the state’s expectation remains the same as it was in the late 1990s: teachers will teach and students will attain the knowledge and skills contained in the state’s Curriculum Frameworks (aka content standards). Students graduating from high school will be Proficient, Meet Expectations, be college-and-career-ready or whatever the current term is for be prepared for postsecondary success.

MCAS has served as a convenient straw man for the teachers’ union to attack for the past 25 years, but their real issue has always been with the standards behind the test. They didn’t talk much about the state content standards during the referendum campaign. They talked about the poor kids who struggled to pass the test and about giving professionals the freedom to decide what to teach and how to teach it. Nobody likes tests. Everybody likes standards.

The argument that teaching was constrained because MCAS didn’t assess the full depth and breadth of the English language arts, mathematics, or science standards has always been laughable. But not nearly as inane as the argument that the state’s decision to test only three of the content areas mentioned in the law detracted from districts’ ability to teach those other content areas. Apparently, the test giveth and the test taketh away.

If teachers were teaching the standards students would have been meeting the MCAS-based graduation requirement; and you know what, virtually all of them have been meeting it since the requirement was first established in 2001. And from the release of those 2001 results, the roar of opposition to the graduation requirement dwindled to a whimper and whine. That was the status quo until the pandemic pause and the backlash against standardized testing provided the teachers’ union an opening for a referendum. And here we are.

So, back to the question asked at the top of this post.

What Comes Next?

The MCAS test-based graduation requirement and its low bar have been removed. The referendum changed the language of the law to read that students will now meet the state’s graduation requirement “by satisfactorily completing coursework that has been certified by the student’s district as showing mastery of the skills, competencies, and knowledge contained in the state academic standards and curriculum frameworks.” Mastery!

If those words have meaning and are not merely lip service then this may be a case of OK, you caught the car you’ve been chasing for 25 years, now what are you going to do with it.

The dirty, little, not-so-secret is that mastery of the state’s standards is a much higher bar and a much heavier lift than anything ever required by the MCAS graduation requirement. It is a bar that all evidence, test-based or otherwise, over the past three decades suggests that a significant percentage of students in the state are unable to meet.

I would have more faith that with the MCAS graduation requirement removed the focus would now shift toward understanding the underlying reasons why 30 years after the Education Reform Law of 1993 the majority of students in the state are not meeting the standards if that had been the argument presented during the referendum.

As I wrote nearly a decade ago in Educating Students for Success, when Massachusetts was considering whether to adopt PARCC, it’s time for states to radically rethink the design of their state assessment programs. My fear is that in Massachusetts that conversation will be further delayed as the state and legislature and local educators try to figure out what to do without the MCAS graduation requirement.

A Reality Check

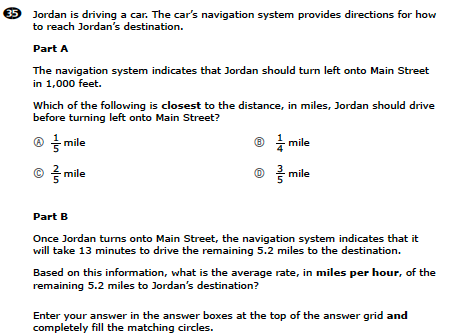

I have made the claim throughout this post that the MCAS graduation requirement was a low bar, but how low was it. To close this post, I’ll let the test speak for itself.

Mathematics has long been regarded as the gatekeeper when tests are used for graduation. On the tenth grade 2024 MCAS Mathematics test students in the Class of 2025 or prior had to earn 14 of 60 points (23.3%) to pass the test. Beginning with the Class of 2026 and the new higher standard, the passing score jumped to 15 points.

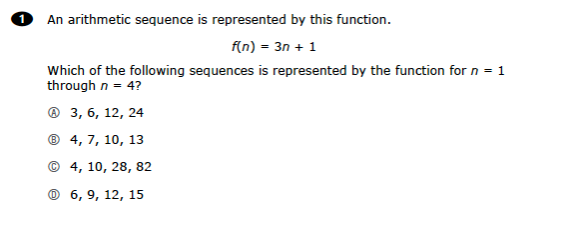

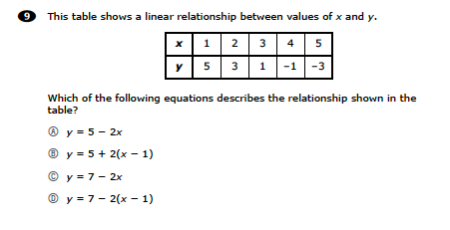

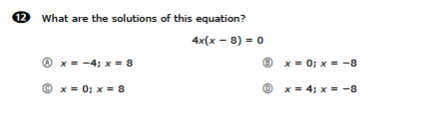

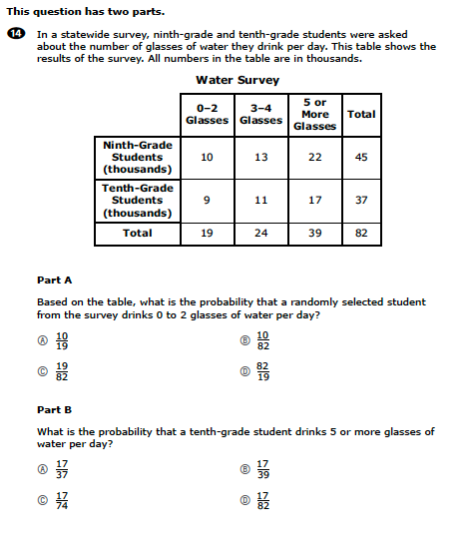

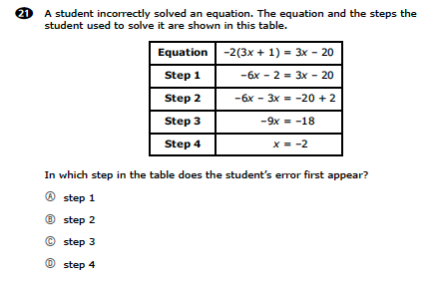

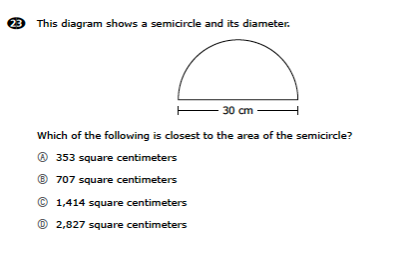

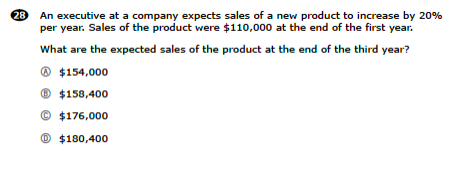

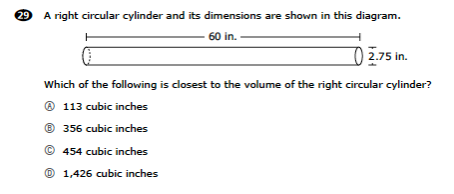

What level of mathematics knowledge and skills is required to earn 14 or 15 points? The set of questions below pulled from the released paper version of the spring 2024 test answer that question. Most require arithmetic, arithmetic reasoning, or some basic Algebra 1. I included one basic probability item just for fun. Students are provided formulas.

It’s true that to get to these questions, students would have to wade through others containing more “mathy” looking symbols and language and a bit too much rotation, translation, and dilation for my old-school tastes, but nothing beyond Algebra 1 and Geometry. However, through the long hours of test preparation these students have endured, I’m sure that someone would have mentioned both the likely passing score and the presence of these items. [sarcasm thinly veiled]

Image by Clker-Free-Vector-Images from Pixabay

Selected Test Items

One thought on “Farewell, MCAS Graduation Requirement, and We Thank You”

Comments are closed.