Despite persistent (and accurate) complaints about its continued reliance on standardization and overuse of multiple-choice items, state testing has changed dramatically since I entered the field in 1989. Perhaps not as much, as quickly, or in all of the ways that many of us envisioned at the time or would like to see today; nevertheless, all should agree that state testing is significantly different now than it was then and that the future promises even more changes.

Those changes have come in many forms. Some changes are related to the content and the format of the test. Many others are related to who is taking the test and how they are tested. Still others are related to how test scores are reported and used; including the level of precision required and the stakes associated with the use of those scores. Finally, one of the most important changes is not directly related to the tests or testing, but rather to the expectation of improved performance over time.

Over the same time period, equating has become a more critical component of the state testing process. On one level, that assertion is blatantly obvious given that for the first 25 years or so of the test-based accountability era of state testing (i.e., 1965 – 1990) state testing was characterized by the use of commercial norm-referenced test batteries and the need for equating test forms from year to year was nonexistent.

On a deeper level, we want to be able to state with confidence that students have been held to the same standard across years, that test scores are comparable (i.e., interchangeable) across test forms, and that the particular test form administered is a matter of indifference to the student. Of course, we understand that idealized level of comparability is purely theoretical (see DePascale and Gong). But we’re willing to live with that if we can come close enough for government work, the governments and works in this case being state testing and federal accountability.

My premise, however, is that with each major changes in state testing it becomes more difficult to make those claims with the same level of confidence, and moreover that the cumulative effect of those changes has brought us perilously close to the limit of our ability to apply traditional equating procedures in a way that allows us to make those statements with any conviction; a tipping point if you will that requires that we reconsider our equating procedures, claims, or both.

The Starting Point

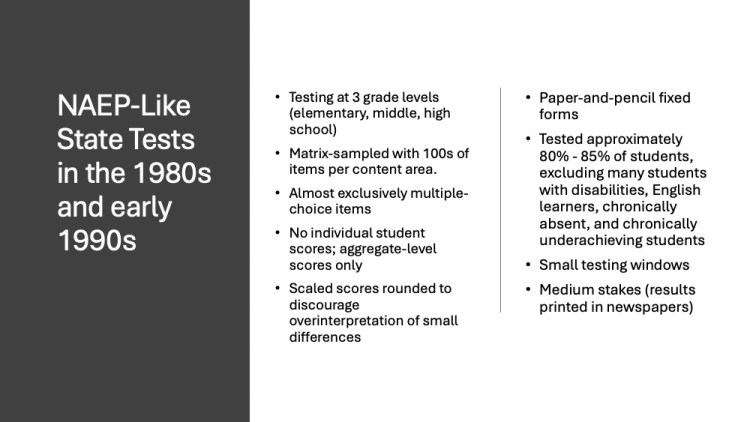

As stated above, the dawn of equating in state test can be linked to the shift from NRT to standards-based tests that began in the mid-to late 1980s and took hold in the early 1990s. What are some of the key characteristics of those early NAEP-like state tests that are relevant to equating?

Also, there was little expectation at that time that state performance would change from one year to the next. In this pre-Education Reform period, “equity” more than “excellence” was the primary focus of Title 1 and emerging special education laws.

All in all, not the best situation from a number of perspectives, but a fairly comfortable environment for a field trying to navigate the transition to equating, IRT, and custom-designed tests.

The Current State Testing Landscape

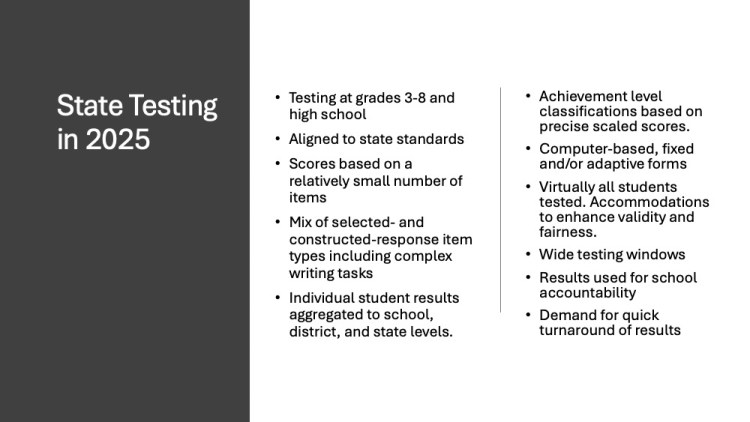

In general, what are some of the characteristics of a “typical” state testing program today?

What Happened As We Moved From Point A to Point B

The graphics above show that state testing looks and feels significantly different in 2025 than it did in 1990. We can list education reform, federal legislation, and a desire for more authentic assessment as primary drivers of those changes. For our purposes, however, specifically what are the biggest changes that make equating more challenging?

- Education Reform and the Expectation for change in performance

Simply put, inserting an additional unknown into the process makes equating more challenging.

- Emphasis on accessibility and inclusion leading to a decrease in standardization

There must always be a tradeoff between standardization and flexibility, but the question is where is the line that cannot be crossed. Which additional accommodation will push us over the line? Which change in testing time, expansion or removal of testing windows, or perhaps even order of test administration?

- Introduction of constructed-response items and additional item types

When does the added dimensionality due to multiple item types become too much for our unidimensional approach to equating to handle? How far can we push the use of multiple IRT models to generate a single test score?

- English language arts – combining reading and writing

Initially, combining reading and writing to produce an English language arts score simply involved computing a composite score. That approach was quickly replaced by attempts to calibrate reading and writing items together – primarily because we needed a way to link writing prompts from year to year. Frankly, it’s been a challenge from the start.

- Increased demand for precision

The need for more precision due to an increased emphasis on individual student scores and increased stakes associated with changes in test scores significantly reduces (if not removes) the margin for errorthat once existed and allowed us, for all intents and purposes, to ignore error introduced by and during the equating process.

- Higher standards and lower performance

The gap between students and items has grown wider as more complex content standards have been introduced and more students have been included in testing. It doesn’t appear to be a gap that is closing a year or so after the introduction of new standards or a new test, as we once expected. That gap places a strain on our ability to calibrate items and equate test forms.

- Computer-adaptive testing

The siren song of adaptive testing makes it easy (and perhaps necessary) to forget many of the factors that we once thought affected equating when we constructed test forms – or even to forget that we are still equating. From an equating perspective, how well do we understand what’s needed to build and sustain the large item banks required for adaptive testing.

- Return to a reliance on external item banks and placing a lot of trust in IRT

It also appears that one lasting effect of the consortium era is the demise of custom-developed state tests and a return to a reliance on external item banks as a source of new test items. Building operational test forms based on parameters of items from a variety of sources that have never been administered together strains the system.

Where Do We Go From Here?

What comes next for state testing and equating? Where is Point C in relation to Points A and B?

It’s certainly possible that with regard to end-of-year state tests we will see something of a retrenchment, a U-turn if you will, in which state tests in 2030 “look” more like their 1990 ancestors in terms of a decrease in the number of grade levels tested, less focus on individual student scores, and an increase in the use of matrix sampling increasing the pool of items available for equating.

But what about state testing as a whole?

Whatever happens with on-demand, end-of-year state tests, it’s likely that state testing will continue down the path of increased complexity, increased personalization and individualization, and increased flexibility in administration as interdisciplinary performance tasks are embedded within curriculum and administered by schools.

What will equating look like? What will it need to look like?

How do we ensure that we are ready for the demands that will be placed on the field to link “test forms” to produce comparable results?

What is the research agenda for state testing, including equating? Who is responsible for developing that agenda, funding it, designing research studies/analyses, and seeing them through to completion?

Complete answers to those questions are beyond the scope of this post (and perhaps beyond my scope), but I can state here that sufficient answers will not come from ad hoc or one-off studies conducted by states and/or their assessment contractors in the midst of operational testing.

Same items and/or same people

Amidst all of the changes to state testing, we’ve clung to the bare minimum in terms of our conditions, requirements, or assumptions for equating: same items or same people. And to be honest, we immediately and reflexively relaxed same people to mean randomly equivalent groups of people. But we know that there’s more to equating than that – more assumptions. Dorans and others warned us about extreme equating and the dangers of extreme assumptions and presumed linkings. Mislevy has painted a sociocognitive picture worthy of Picasso. We know that you can only bend assumptions the system so far before it breaks.

I don’t think that we’ve broken anything yet, but it does feel like we are quickly approaching the limit.

Header image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

One thought on “Approaching The Limit of Equating State Tests”

Comments are closed.