Have you heard the one about the economist who dropped his wallet one night? He started looking for it once he reached the next streetlamp, because the light was better there.

I read two versions of the text above, a joke serving as a parable, last week. The version above is from Moral Ambition, the latest book written by Rutger Bregman. An alternate version involving a bar, a drunk, and car keys appeared in a recent blog post by Scott Marion. As with any good parable, the text is open to multiple interpretations.

In his post, Marion used it to caution state leaders and policymakers against the quick fix of “changing a test to improve student achievement,” noting that “it makes sense to reflect on the test, but changing it doesn’t solve the problem.” He goes on to discuss the “hard work” of addressing and solving the underlying problems affecting student learning and achievement.

The lesson that Bregman hopes his effective altruists and other reformers take away is somewhat different:

By fixating on what they could measure, they overlooked a world of possibilities.

It is this second interpretation that I would like to focus on in addressing the initial issue raised in Marion’s blog post; that is, state leaders and policymakers “rightfully wondering if their students are learning, but their assessment system is preventing them from showing what they know and can do.”

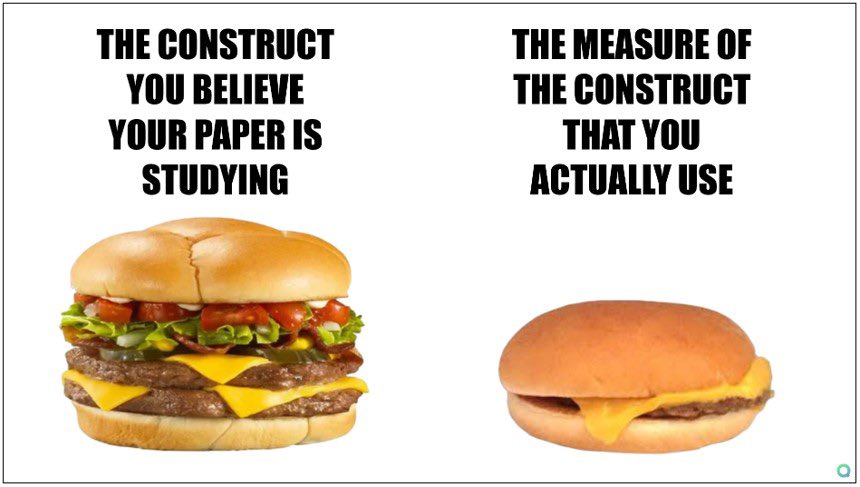

The question those state leaders are pondering is not new. It is one that critics of standardized testing have been asking since the days of norm-referenced tests consisting of multiple-choice questions – accepting for the sake of argument that we have moved beyond those days. Yes, the claim has often rung hollow as a weak attempt to explain away poor school performance. Nevertheless, as we all know, the fact remains that state tests measure a fairly narrow range of student knowledge and skills, most often those that we can most easily measure. The Quantitude Podcast hamburger meme pops to mind.

Further, we’ve known from the beginning that knowledge and skills in reading, mathematics, and science (i.e., the subjects assessed on state tests) are a mere fraction of the important stuff (yes, that’s the technical term) that goes on in schools and that we expect students to learn.

Finally, if the question is still being asked by state leaders and policymakers 25+ years into the era of test-based accountability and a quarter of the way through the 21st century, perhaps it merits serious consideration, particularly if one considers another oft-quoted admonition:

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

All of which gives credence to state leaders and policymakers “rightfully wondering if their students are learning but their assessment system is preventing them from showing what they know and can do.”

State Assessment As Streetlamp

Leaning into the parable, the state assessment as streetlamp metaphor works on multiple levels. First, there is the function of streetlamps. Second, there is the manner in which streetlamps are deployed. Third, consider the improvements that have been made to streetlamps over the years without significantly altering their original functionality. Let’s review quickly.

Function

An individual streetlamp is designed and intended to illuminate, literally shed light on, a small tract of land. The parallels to state tests being self-evident.

Deployment

Streetlamps are deployed strategically where they are determined to be needed and will do the most good. Additional streetlamps are added, as needed, as conditions change (e.g., greater population density, increased traffic, change in neighborhood use, safety issues). The collection (or system) of streetlamps covers more ground, while each individual streetlamp performs its original function.

On the busy avenue where I grew up in Boston, streetlamps lined the street. I still remember my fascination that day in the mid-1960s that the streetlamp went up directly outside of our triple-decker house, its light shining almost directly into my grandmothers second floor bedroom. Where I live here in Maine, there are streetlamps at intersections off of the main thoroughfare through town, but I encounter none as I make my way through the neighborhood.

Similarly with state tests, we began with the strategic placement of tests at the end of grades 4, 8, and either 10 or 12. Several states added a grade 3 Reading test. In Massachusetts, after a couple of years of testing, we felt that the unlit gap between grades 4 and 8 was too much in mathematics and inserted a grade 6 mathematics test. NCLB increased their frequency, with annual tests at the end of grades 3 through 8. Many districts, and some states, inserted additional tests in the interim between end-of-grades.

What’s important to note is that for the most part all of those tests did the one thing that state tests were designed to do; that is, shine a light on overall student proficiency at particular point in time. Additional tests simply did it more frequently.

Improvement

Streetlamps have certainly come a long way since pre-electricity days and the old lamplighter who would trip a little light fantastic and who made the night a little brighter wherever he would go. Instead of gas-fueled flames, we now enjoy dark sky compliant streetlamps with LED bulbs. Electricity added efficiency to the process of lighting streetlamps each day. Photosensors that turned the lights on and off automatically added even more efficiency. Changes to the type of bulbs improved both efficiency and effectiveness. Through all of the improvements, however, streetlamps continued to perform their same well-defined and limited function.

To the chagrin of many, the same can be said of state tests.

Add-ons

Although I will hold off on addressing accountability systems and their effects on the question at hand until a later post, I would be remiss in not acknowledging the consequences, positive and negative, intended and otherwise, based on how test results (and streetlamps for that matter are used). Who among us has not altered their driving behavior in some way based on cameras or radar added to streetlamps, traffic lights, etc.

Out of the Darkness on State Assessment

As a psychometrician, I have the utmost confidence that today’s state tests are measuring what it is that they measure very well. As a state assessment specialist, however, I have known since the 1990s and the push for more authentic assessment that a stand-alone, external standardized test administered at the end of the year is inadequate to fully assess student proficiency on complex standards, even in the tested content areas. As a practical matter, I accepted that state tests were close enough for government work.

I knew also that there was so much more to schools than student achievement in reading and mathematics. At least through the mid-2010s, however, I accepted the two-part argument that a) achievement in those areas was the foundation (that is, a prerequisite) for all else cognitive and academic that schools were trying to accomplish and b) that those cognitive and academic tasks were the school’s highest priority. Since as early as 2015, and certainly since the pandemic, views of the purpose of schools have changed. Unchallenged certainty about the preeminence of reading, writing, and arithmetic (if you will) is now the argument that rings hollow.

For many reasons, some for the better and some for the worse, priorities, purposes, and preconditions of schooling have changed. Changed to the point where state leaders and policymakers may be “rightfully wondering if their students are learning but their assessment system is preventing them from showing what they know and can do.”

If we truly believe that we are in the midst of a revolution in public schooling, then like the drunk and the economist we must be willing to look beyond the things that we can easily measure, or simply those that we have chosen to measure in the past. We must be open to the world of overlooked possibilities.

The world and the daily experiences of students have changed immeasurably since the CCSS were adopted in the early 2010s. Yet, our state tests continue for the most part to measure the same things in the same way. Incremental improvements focused primarily on increasing efficiency. We have to acknowledge that perhaps priorities have changed, and that we might be looking for answers in the wrong place.

Header image by P_K_D from Pixabay

2 thoughts on “Looking In The Wrong Place”

Comments are closed.