Ultra processed foods. UPF

While scrolling through posts on your favorite social media platform, who hasn’t come across a video or graphic comparing the ingredients in a homemade v. a store-bought ultra-processed lemon cake. [OK, I’ve now used all three of the apparently acceptable spellings found in articles about UPF. Take your pick.]

The cake from the store has a long list of ingredients containing words that I’ve never seen and cannot pronounce. The homemade cake, in contrast, contains flour, sugar, eggs, butter, lemon zest, lemon juice, baking soda, and salt. The difference is staggering, and the message is clear. Well, actually, two messages.

The first is the message I have heard my entire life from my grandmothers, mother, mother-in-law, and wife along with an uncle and my father-in-law:

There is nothing as good as what you make at home!

Just close your eyes, click your heels three times, and I’m sure you can hear it, too.

The second message, of course, has to do with the dangers of ultra-processed foods. The dangers of ingesting foods that have deleterious effects on our bodies while also affecting our minds; that is, betcha can’t eat just one.

Who needs to invent deep state conspiracy theories when you have ultraprocessed foods?

But the other night, as I was sitting on the couch watching yet another series on Netflix that will be canceled without a satisfying resolution, scrolling through various timelines on my phone, and mindlessly going for a handful of Goldfish crackers, I began to ponder whether there was an educational assessment equivalent to UPF.

And it didn’t take long, perhaps a handful of two, for me to realize that our version of UPF are ultraprocessed test scores (UPTS).

It’s not a one-to-one correspondence, of course. Nobody’s mother, and certainly no psychometrician, has ever made the claim that there’s nothing as good as teacher-made tests and test scores. And the research on the long-term effects of our ultraprocessed test scores on physical and mental health outcomes is inconclusive at best.

In just about every other important aspect, however the similarities are striking.

Ultraprocessed Test Scores (UTPS) – What Are They?

While any description of UPTS could certainly include our own unique list of Greek- and Latin-rooted hard-to-pronounce words, the deleterious feature of test scores that I want to focus on in this post are the steps that we take in processing student responses and producing test scores that make it increasingly difficult to draw a direct connection between the test score that we report for a student and the work produced by that student.

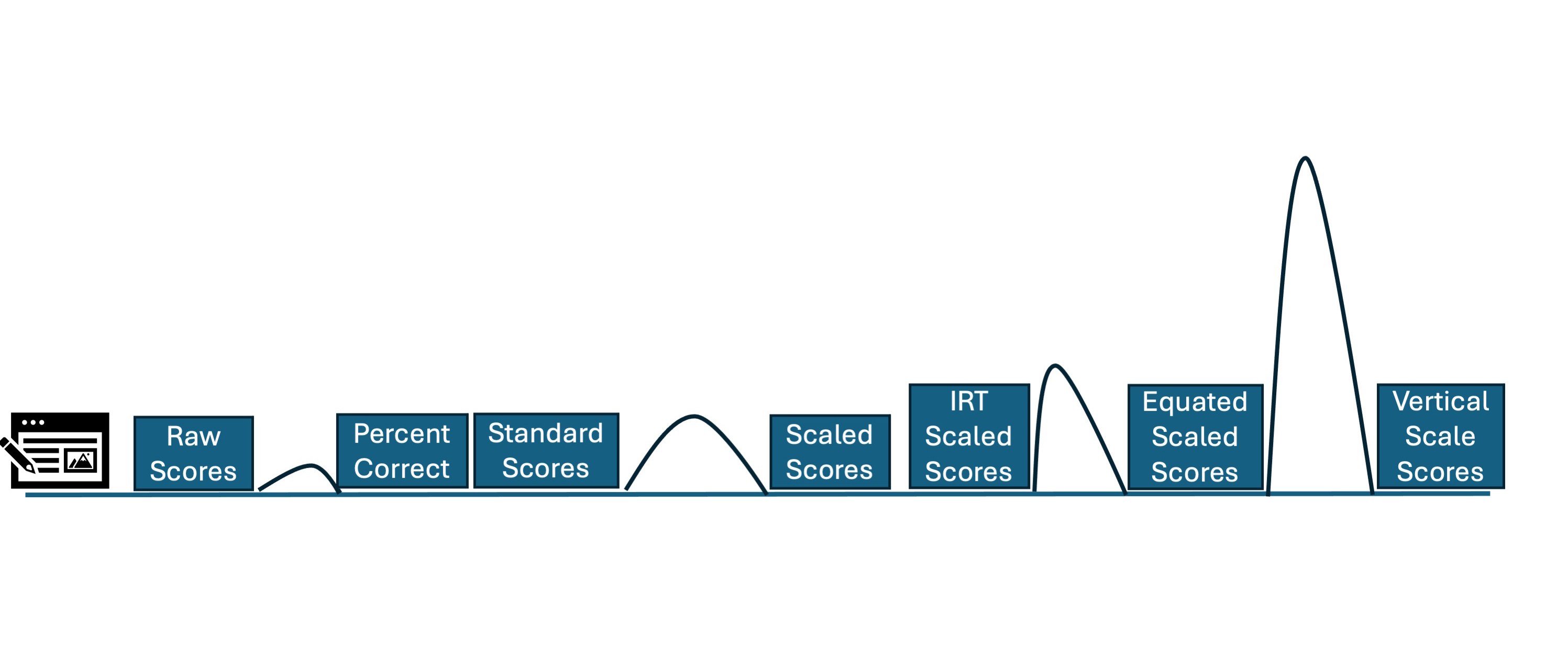

The graphic below contains seven types of test scores which should be familiar to all of us. They are the building blocks of test score reporting, beginning with raw scores and proceeding through percent correct, standard scores, scaled scores, IRT scaled scores, equated scaled scores, and vertical scaled scores. The ordinal depiction presents the test scores in terms of their “distance” from the student work on which they are based, both in terms of how much processing has been done to them and how difficult it is to “see” the original student work from the resultant test score.

By the time that we have moved from a student’s raw score on a test to reporting a score on a vertical scale, the connection between test score and student work, like the S.S. Minnow, has been lost; and attempts to make connections between the two produce nothing more than 30 minutes of pure comedy. Even proponents of vertical scales have to admit that interpretability in terms of a direct connection to student work is not one of the claims that you can make about vertical scales.

By the time that we have moved from a student’s raw score on a test to reporting a score on a vertical scale, the connection between test score and student work, like the S.S. Minnow, has been lost; and attempts to make connections between the two produce nothing more than 30 minutes of pure comedy. Even proponents of vertical scales have to admit that interpretability in terms of a direct connection to student work is not one of the claims that you can make about vertical scales.

Further, those seven building block scores presented above are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to UPTS.

Where would we place Achievement Levels in terms of connection to student work? I bet that we all like to think that the connection is strong but given the point in the process where we normally set achievement standards, the connection to the actual performance of an individual student on a given item or standard is weak, at best; and no, embedded standard setting won’t make that connection any stronger.

And what to make of growth scores? Whether you prefer highly-processed scores like student growth percentiles or deceptively simple difference scores on vertical scales, you have likely already become addicted to the sweet siren song of growth scores. Like UPF, the “beauty” of growth scores is that they not only require more testing but actually get you to want more testing – betcha can’t eat just one.

Then there are the unitless scores like percentile ranks, effect sizes; and perhaps the “scores” produced by diagnostic models (I’m not sure). They fit in at various stages along the processing continuum.

Let’s not forget whole group and subgroup scores, conditional or not; and also composite scores like school accountability ratings – the Froot Loops ® of large-scale, summative PK-12 educational assessment.

Of course, no discussion of UTPS would be complete without mentioning the process-iest of all processed test scores: NAEP Scores (scaled scores and achievement levels). Even before considering the actual processing involved in producing a NAEP scaled score, in terms of processing time alone, one could make a plausible case for NAEP scores as the gold standard, the uber-ultra-processed test score. Note, we are barely more than 2 weeks away from the release of the 2024 NAEP scores.

Clearly, there’s a whole lot of processing going on, and as a field, we have become much more focused on the processing than on the original product. And that’s a bad thing.

But NAEP scores are good, right? And important?

And we need to equate.

And I still don’t hear anyone making the argument that there’s nothing as good as test scores from teacher-made tests.

So, what gives? How do we process this paradox? Where do we go from here?

Some Things in Moderation, Everything For a Reason

There are valid reasons why we bake a cake from a mix instead of from scratch or buy that sheet cake at the store, and there are valid reasons why we process test scores.

The recent weeklong NY Times series on UPF offered the two valuable takeaways:

- The goal is not to totally eliminate all UPF from our diets, but to be more mindful and considerate in how many and which UPF we consume, and how often we consume them.

- Not all UPF are necessarily bad for you and homemade foods are not, by default, necessarily good for you.

In short, we need balance, and more importantly, we need to make well-considered purposeful decisions about the foods that we eat and the test scores that we produce and report.

Careful consideration will be particularly important as we move forward because I see our field being pulled in two directions: toward opposite ends of the processing continuum.

On the one hand, I see computational psychometrics, data science, AI, and the like pulling in the direction of even more processing: complex modeling of more complex student behaviors.

On the other hand, I see an increased focus on more complex, curriculum-embedded performance tasks, a shift from overall proficiency toward specific competencies and mastery, and a renewed interest in learning progressions all pulling in the direction of placing more emphasis on actual student work; that is, the product and performance produced by the student.

I don’t know how things will play out, but I am certain that we are well beyond the point where we can encourage or allow two groups of professionals to wander off in different directions, separately pursuing their own pathways. Been there. Done that.

We assessment specialists have to accept that not everything has to be equated and placed on a scale, sometimes a rubric will do just fine. And the other 99% of the education world has to give a little as well. Processed test scores consumed in moderation can be just fine.

Let’s Start At The Very Beginning

It won’t be easy to change our mindsets or behaviors, but like the NY Times series recommends regarding UPF, I advise us to start small.

How small?

Let’s start at the very beginning with our conception of raw scores – a term, by the way, that Google and its AI helper tells me was coined by Alfred Binet. I’ll have to check with Derek Briggs on that. Anyway. I’ve never thought about it before, but in the context of this post our use of the term itself, raw score, is telling.

It may be a cultural thing, but in our Western, industrial, quantitative, carnivorous culture, there is a connotation attached to the word “raw” that implies that further action is not only desirable, but necessary. Something, or someone, described as raw is “unprepared or imperfectly prepared for use,” and is characterized by words such as unpolished, unfinished, or unrefined.

Other fields, cultures, or generations, however, tend to emphasize the unaltered, pure, or natural aspects of the term raw – even in their definitions of the term raw score. But for us, the raw score is merely a quickly forgotten starting point.

The joint Standards (2014, p. 222) defines a raw score as “a score on a test that is calculated by counting the number of correct answers, or more generally, a sum or other combination of item scores.” Like many things in the Standards, that definition is probably a phrase too long, but at the same time and in important ways is incomplete. The paradox and inevitable consequence of consensus.

As a starting point, let’s resolve that as we move forward in 2025 with revising the joint Standards that we arrive at a better, more holistic definition of raw score – one that not only supports necessary processing, but also respects the student and their original work.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

You must be logged in to post a comment.