Have I Been misReading Our Math Problem?

For as long as I can remember it has been accepted as an article of faith that the United States has a mathematics problem. Even more than an article of faith, it has long been something of a badge of honor in the U.S. to be bad at math, much more so than reading. In popular culture, people go to great lengths to hide their inability to read, while being bad at math often makes them one of the in crowd. Math phobia is one of the few phobias that it is still socially acceptable to admit to having.

Reading is a leisure activity with bestseller lists and book clubs fronted by celebrities. Math, on the other hand, is a chore. So much of a chore that people choose to pay others to complete the one annual math task – completing their tax returns. Just how badly do people want to avoid math; while we spent $25 billion on books last year, the amount spent on tax preparation exceeded $100 billion.

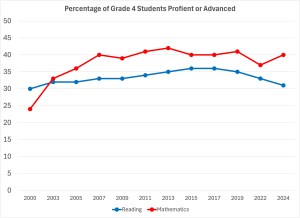

Imagine my surprise, therefore, when reviewing the NAEP results released last week and realizing for the first time that fourth grade students have been performing better in mathematics than reading regularly for the past two decades or so. Even among eighth grade students, the percentage of students performing at the Proficient or Advanced levels in mathematics exceed those in reading by 1 percentage point on the last pre-pandemic assessment in 2019; and student performance in the two content areas remains close on the two post-pandemic assessments.

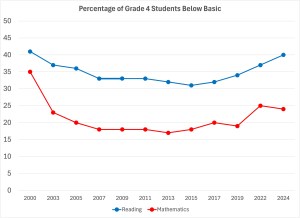

Results at the other end of the achievement level scale are even more striking, with a large gap in the percentage of students performing Below Basic in reading and mathematics.

Why then is there so much focus on our mathematics problem?

Out-of-control credit card debt, car loans and home mortgages that people have no chance of paying off, woefully underfunded retirement plans, and counterintuitive voting patterns might be real-life, long-term answers to that question.

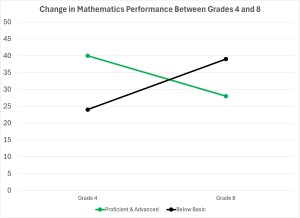

For now, however, I’ll keep the focus on schools and test performance. In particular the change in mathematics performance between grades 4 and 8.

The Bermuda Triangle of Mathematics Performance

Even while celebrating its position as one of the nation’s lone bright spots in the NAEP 2024 results, Louisiana’s chief state school officer commented on the performance dip between fourth and eighth grade. As many have noted over the last week, achievement level results in mathematics at the national level pretty much flips between grades 4 and 8.

But the dramatic drop in mathematics between fourth and eighth grade is hardly a new phenomenon. We experienced a similar drop-off in Massachusetts in the late 1990s in the early days of the MCAS program. In an effort to uncover when the decline was occurring we introduced a Grade 6 Mathematics test: the first expansion of the program back in the pre-NCLB days of testing at grades 4, 8, and 10. At approximately $1 million per test, it was not a decision that was made lightly. Neither was the governor’s proposal to test every mathematics teacher at schools that did not meet a certain performance threshold.

Even with 20+ years of data in hand, however, the smoking gun, a precise and detailed explanation for the drop in performance between elementary school and high school eludes us. Several plausible explanations have been offered, including:

- Weakness or gaps in students’ foundational skills in mathematics through the fourth grade. Even though performance is better in fourth grade, a majority of students fail to reach the Proficient benchmark.

- The shift from in content from concrete, operational skills to increasingly more abstract concepts.

- The lack of expertise or specific training in mathematics of educators tasked with teaching mathematics, particularly at the elementary school level.

And my personal favorite theory, a mathematics curriculum that continues to pile skills on top of skills all the way through calculus in the twelfth grade. One that never makes the shift from learning mathematics to using mathematics and consequently fails to engage the vast majority of students. (“When and how and I ever going to use this?”)

In the end, the reasons listed probably all contribute in some degree to the mathematics. They also share something else in common:

They are all focused solely on mathematics.

As I reviewed the both the NAEP results in reading and mathematics these past few days, it finally occurred to me, by focusing solely on mathematics answers to our mathematics problem, we might be overlooking the biggest source of students’ struggles with mathematics: their ability, or more importantly, their lack thereof, to read.

Learning to Read to Read to Learn Mathematics

We, or at least I, have a tendency to focus on the NAEP results one content area at a time because they are presented that way. Even on the website you have to back all the way out of one content area to view the parallel pages containing the other content area results. As we all know, however, learning doesn’t occur in content area siloes.

And as students move beyond fourth grade, reading and the skills that it comprises become an increasingly important part of learning, engaging in, and succeeding in mathematics.

Virtually all of the mathematics that students encounter in middle school and high school is presented in written form. They have moved beyond naked computations to problem situations, theorems, postulates, etc. As a starting point, they must be able to read and understand the problems being presented. The same applies to adults reading credit card terms, loan applications, and streaming service plans.

Next, students must apply the very same skills that are central to reading comprehension in order to be able to determine which parts of the information being presented are signal and which are noise before they can identify which processes, procedures, and skills to pull from their mathematical toolbox.

Finally, students must be able to communicate. From Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell early in the 20th century to the NCTM Standards at the end of that century to the Common Core State Standards in 2010 the message has been constant and clear: communication is a key component of mathematics.

It only makes sense that as students struggle more with reading that they are not going to be as successful in mathematics. At least one NSF-funded study found a one-way relationship between students’ reading anxiety and motivation and their performance in mathematics. We’ve known for a while that the CCSS mathematics folks didn’t do us any favors by not integrating standards and practices, but here is another reason why it’s clear that we must understand the connection between the two.

Yes, there a number of ways that we can and must improve mathematics curriculum and instruction and we certainly must do a better job of supporting early childhood acquisition of fundamental skills in and out of formal settings.

I am convinced, however, that there will be a ceiling on how successful we can be in solving our mathematics problem until we tackle our reading problem.

Image by Moshe Harosh from Pixabay

You must be logged in to post a comment.