Fundamentals and Flaws of Standards-Based Testing is a forward-looking reflection on my three-decade career in large-scale state testing.

Throughout the book, I share lessons learned and unanswered questions from my personal experiences across three decades in state testing; an unplanned and unexpected odyssey that began in 1989 as a young data analyst at an upstart startup, Advanced Systems in Measurement and Evaluation, Inc., whose founders Rich Hill and Stuart Kahl had a vision for a brave new world of PK-12 state testing. I could not have anticipated the twists and turns in the long and winding road that followed.

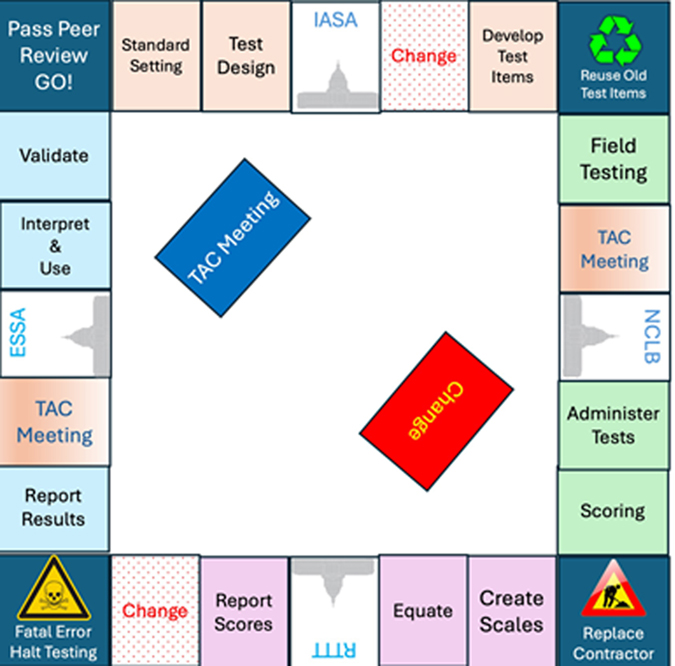

Three-plus decades later, that world seems once again poised to make a giant leap into the unknown and untested. In the book, I walk step-by-step through each major phase of the testing process from standard setting to validation and back again, identifying and discussing decisions made (or not made), questions that we have not been able to answer (and some that we have not thought to ask), and challenges still to be met.

The biggest takeaway will not shock anyone:

- As we were all taught on first day of our first course in testing or educational measurement, an individual test score is simply a snapshot of student performance at one moment in time. At the group level, a well-designed test might produce a picture that is sharp and quite detailed. As we zoom in to the individual level, the image becomes fuzzy and pixelated, and additional information almost always will be needed to place the test score in context and to support its interpretation and use. We know this. We must act accordingly.

Two other general takeaways:

- As a field, we have become too inward-looking, obsessed with improving the technical quality and precision of standards, items, scores, and scales often forgetting that the true measure of the quality of our test instruments and scores has always been based on how well they describe and predict knowledge, skills, competencies, behaviors, etc. of real students in the real world outside of the testing environment.

And the related point…

- State testing, and perhaps large-scale educational assessment in general, has always been primarily a data collection activity. As we move through each phase of the testing process, almost all of the questions we ask and decisions we make are centered on what data we need to collect to support the inferences that we need to make and how best to collect that data as efficiently as possible. For the better part of the past two decades, we have been asking ourselves how to build a better test when the more appropriate question to ask should have been how best to collect the data that we need.

In the coming weeks, I will devote individual posts to specific topics addressed throughout the book. To whet your appetite, in this post I offer a brief statement summarizing a key point from each chapter.

Standard Setting, Achievement Levels, and Cutscores

Even as we continue to improve our processes and procedures to connect standards and test items to achievement standards, we must not forget that student proficiency exists outside of the test and that it is not the role of psychometricians or purpose of the test to define proficiency.

Designing Test Forms and Assessment Programs

Form Follows Function. Far too often, we have allowed constraints on form to define and limit function, as the field continues to struggle to find the answer to the same question we were asking in 1989; that is, how to move beyond on-demand end-of-year tests toward more authentic and comprehensive assessment of student performance.

Developing Test Items and Test Forms

We have placed far too much responsibility for making critical decisions and solving complex problems on the shoulders of item writers, test developers, and assessment/bias review committees. These tasks include instantiating state content and achievement standards as well as defining and operationalizing complex issues such as fairness, bias, and now cultural relevance; most of which are high-level policy decisions that rightly belong outside of the purview of the state test

Field Testing New Test Items

At the same time as the field has become more dependent on the results of field testing to populate operational tests, we have become less deliberate and thoughtful in selecting field test samples best suited to support the inferences we intend to make, falling into a pattern of relying too often simply on representative samples from “populations” of convenience.

Administering State Tests

Test security and personalization of the test and testing experience remain as wicked problems to solve. By far, however, I think that our biggest challenges remain in resolving issues related to time: testing time and more importantly, unpacking and better understanding issues related to the complex relationship between time and student proficiency.

Scoring Student Responses to Test Items

The immediate future of scoring student responses is automated, and the long-term future ultimately will rest in the hands of artificial intelligence. There are key aspects of the scoring process however, that we need to better understand before handing the entire enterprise over to the machines. For example, is the unreliability built into the accepted processes and procedures for human scoring a feature or a bug; and what will the impact on student scores be if/when it is removed?

Creating Test Scores and Reporting Scales

How do we resolve decades of decisions designed to maximize the technical quality of group-level, cross-sectional scores used for institutional purposes with the field’s inexorable shift toward the individual, the formative, and the desire for actionable information to support instruction? Keeping in mind that, as described above, an individual student test score on a single test remains a sample of 1.

Equating Test Forms Within and Across Years

Since the initial shift of state testing from NRT to CRT in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it is not hyperbole to say that virtually every decision related to the operation of large-scale state testing programs has made equating test forms within and across years more difficult. Those decisions are occurring more frequently and their impact on equating is growing exponentially. Further, the increased reliance on pre-equating only exacerbates the issue by reducing, if not eliminating, our margin for error.

Reporting Test Scores

When will increased interest in subscores, competencies, and individual student strengths and weaknesses reach the tipping point that forces the field to reconsider the decision to define proficiency in terms of a student’s location along a unidimensional scale? And in response to Andrew Ho’s call for communication competency, when will we do a better job of communicating the imprecision in an individual student’s test score and with evidence, communicate decisively about student performance amidst indecision?

Reporting Test Results

One of the casualties of the increased testing and accountability demands of NCLB has been providing external program, curricular, instructional, and background information to stakeholders (i.e., districts, schools, and parents/students) to place state test scores in context. At the same time, an inordinate emphasis has been placed on disaggregating and reporting results by race, ethnicity, and other federally mandated categories without commensurate attention devoted to how we expect that information to be used to improve instruction, particularly as we move from the state level to districts, schools, and individual classrooms.

Interpretation and Use of State Test Results

It’s one of the great paradoxes of our field that we devote so much energy, blood, sweat, and tears to producing high-quality test scores and results, but for most of us involved in state testing, when those scores and results are released our involvement ends. While those in the schools, district offices, and state houses are just getting started with this year’s test, our attention has turned to preparing for the next test administration and the one after that. Before even thinking about better communication, we have to commit to taking a more active role in how the scores and results from our test are interpreted and used.

Validating Test Scores, Tests, and Testing Programs

To be blunt, there is little about the operation of a state assessment program that is conducive to the validation process or incentivizes states to engage in it – and let me be clear, that statement specifically and especially includes the federal Peer Review process.

Are state test instruments, items, scoring and scores, reports and results subjected to extensive review for their technical quality? Most definitely.

Are any of those things and their use subjected to an ongoing validation process? No, not really.

I discuss a number of reasons for this unfortunate state of affairs in the book, but one of the most concerning to me is that our intense inward focus on creating a better, more technically sound tests has led us directly into the most fundamental trap in educational measurement, perhaps psychological measurement, in general; that is, creating a tautology in which it is becomes impossible to distinguish between the measurement instrument and the construct being measured (or content, if you prefer).

Epilogue (and Preface)

I’ll end this post with excerpts from the epilogue and the preface to the book:

State testing, like all fields, must continue to change internally, to improve the ways that we do what we do. Fundamental to improving what we do is being very clear about what it is that we do; that is, we must have an explicit understanding what we are assessing and why we are assessing it.

And as a field that is in service to public education, state testing must continue to adapt and adjust to the meet the changing needs and demands of society that are reflected in our schools.

If there is one other statement that I can make with confidence about the future of state testing it is that it will remain flawed, perhaps fundamentally flawed, but I hope not fatally flawed.

Flaws are part of learning. Flaws are part of change. Flaws are part of innovation and improvement. Flaws are most certainly part of measurement, modeling, and certainly part of educational assessment.

We are trying to model complex human behavior with limited understanding of those behaviors and limited access to data. There will be flaws.

My goal in writing this book is to describe some of the juggling and balancing took place in the assessment programs I was fortunate to play some part in from 1989 to 2019. I hope that by providing a little insight into some of the choices and decisions we made, as flawed as they might have been, and by discussing some of the fundamental questions that we were unable to answer and challenges we were unable to overcome fully I will help the next generation of state assessment specialists make better decisions.

Images by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

Skull & Crossbones Image by OpenIcons from Pixabay