This post begins in the fall of 1983. A young lad with an M.Ed. in his pocket and a song in his heart left home, boarding a plane for the first time on a journey to the hinterland (i.e., Minnesota) in pursuit of a dream – well, at least a doctorate. Rounding out his course schedule that first quarter (yes, the U of M was on the dreaded quarter system at the time), he decided to enroll in an introductory course on behavioral psychology.

Why behavioral psychology?

Possessing that basic level of intellectual curiosity that was common among educated people of the day, but is quite rare today, he simply wanted to hear a different perspective on the topic, after years of hearing of the virtues of cognitive science and vitriol on the evils of behaviorism and the simple-minded thinking of behaviorists. He never expected that professor would become a mentor.

Fast forward a couple of years, our hero, ready to set out on his own, yearned to return to the land of fluffernutter sandwiches, dropped r’s, and outdoor baseball. Before his sojourn came to end, however, he sought the advice of his mentor on a vexing question: How do I choose between behavioral psychology and cognitive science? The Solomon-like, yet Pythian reply:

Unless you’re planning to become a behavioral psychologist or cognitive scientist, you don’t have to choose.

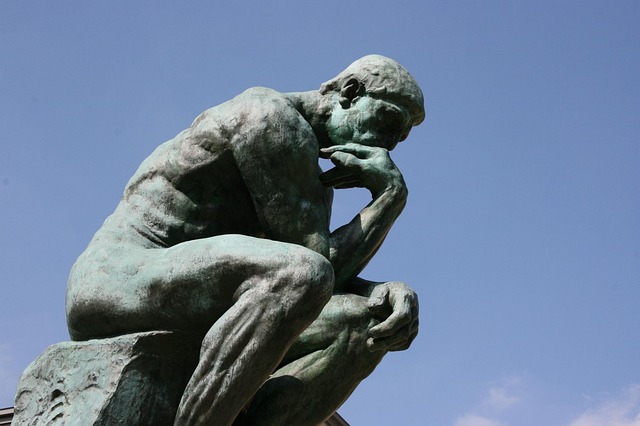

Observing Thoughts and Pondering Behaviors

As humans do, for whatever reason, I tried to resolve my cognitive dissonance between behavioral psychology and cognitive science by seeking out opportunities to merge the two. With the clarity of naivety, expanding the behaviorist concept of “environment” slightly, I concluded that goal of cognitive science was simply to find a better stimulus; that is, to peer a little deeper into the black box to improve the stimulus-response interaction; and in my world, to use that information to improve instruction, itself simply a series of stimulus-response interactions.

Of course, the picture of behaviorism and the instructional applications that I have in my mind are much more complex than teaching a chicken to play tic-tac-toe. Although, that level of training is nothing to laugh at. My father proudly wore his “bested by a chicken at tic-tac-toe” t-shirt until it was threadbare.

In the early 2000s, my colleague published Introducing Students to Scientific Inquiry: How Do We Know What We Know? Described as “providing a bridge between theory and sound instructional practice” the book offers a series of “illustrative case studies” that present “a variety of pedagogical and assessment tools necessary for teaching elementary school students about scientific inquiry.” After reading each of the case studies, my takeaway at the time was awe at the level of thought, care, and attention to detail necessary for educators to create a “constructivist” environment in which “learners can build their knowledge through experiences and interactions”, connecting “new information to their prior knowledge.”

Over time, as cognitive science blended with neuroscience to give us cognitive neuroscience – “the scientific field that is concerned with the study of the biological processes and aspects that underlie cognition” – my unified framework for behavioral psychology and cognitive science, at least as they relate to instruction, solidified in my mind. The “environment” of interest is internal as well as external and involves a complex network of interactions, nevertheless, it all seems to keep coming back to a stimulus and response – this action lights up that part of the brain – ultimately leading to an observable behavior.

Now we are in the age of artificial intelligence. Without ever fully understanding or reaching consensus on an adequate definition of human intelligence, we seem poised to move the conversation from human cognition to sentient, conscient machines; that is, we appear ready to ascribe most, if not all, of the attributes that defined cognitive science to machines. If so, then it would seem to me that any debate between behaviorism and cognitive science or cognitive neuroscience is moot. I don’t have to make a choice because there is no choice to be made. If a then b.

Cogito Ergo Sum

Understanding the details of all of this is beyond my ken. I don’t pretend to be an expert in behavioral psychology, cognitive science, cognitive neuroscience, artificial intelligence, or instruction for that matter. Frankly, it takes enough of my time and energy pretending to be an expert in educational assessment.

That’s fine. Just as I didn’t have to choose between behavioral psychology and cognitive science, I don’t think that I have to be an expert to apply what others are learning about learning to instruction and ultimately to assessment as a component of instruction.

Whether the topic is direct instruction of basic skills, instruction in more higher-order skills related to scientific inquiry, or the acquisition of complex competencies that require the synthesis and application of a host of 21stcentury skills, it seems clear that the keys to instruction and learning are the same as they always have been: establishing a proper learning environment to stimulate desired responses (however complex), providing appropriate, timely feedback when needed, and providing opportunities for repetition and practice.

It may not be behaviorism, and it may not be cognitive science, but it’s certainly not rocket science.

A question that remains, however, is who or what is capable of creating such learning environments or environments for learning. Because although students and student learning are typically positioned as the primary focus of the behaviorism v. cognition debate, the flip side of the equation, the teacher and the teacher’s role, if any, in instruction has never been far from the surface.

As I ponder that question, I’ll close this post with some thoughts that George Madaus expressed on the topic at a 1985 conference on The Redesign of Testing for the 21st Century.

At the heart of teaching is the inescapable element of relationship…

Precisely because it involves relationships, teaching is more often than not spontaneous, unplanned, unpredictable; a creative performance that relies heavily on the subtle interaction between and among students, the class as a whole, and the teacher. No machine can recognize – let alone decipher – the fleeting cues in posture – a yawn, giggle, whisper, or furtive or bored look – and know how to alter its tactics in response. Moreover, you cannot totally define all educational objectives with the overt precision that a computer program presupposes. But most of all, teaching entails a moral and ethical relationship between human beings (Jackson, 1968). No program, no matter how sophisticated, will ever be able to care about, or feel responsible for children.