The winter solstice is upon us. The darkest day of the year, at least for the 87% or so of us who reside in the Northern Hemisphere.

In that very literal sense, the winter solstice is a point of inflection. It’s the point at which we start to gain a bit of daylight each day, little-by-little, minute-by-minute until the summer solstice in June. If one were to graph (or create a visualization) of the amount of daylight each day in the year, the winter solstice would be a point of inflection – as would the summer solstice – points in time at which the graph shifts from concave down to concave up or vice versa. Back in the day, we would have said concave and convex rather than concave up and down. I guess that wasn’t quite accurate, but it served us well for most purposes.

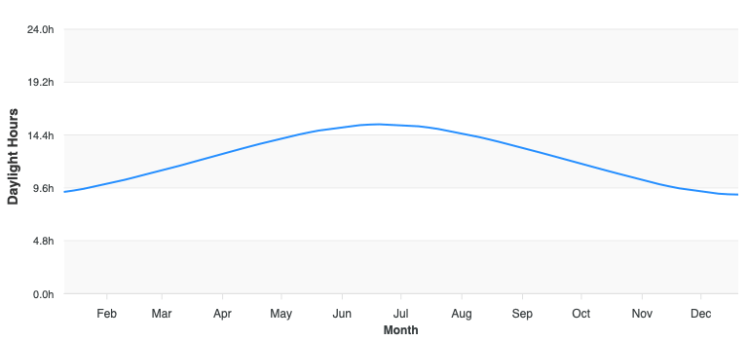

Of course, you don’t really get that whole up and down sense of inflection if you focus on the graph for a single year. As shown here in the graph for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, one year laid out flat from January to December simply gives you a single hump peaking in June, leaving you feeling incomplete, needing to infer the rest.

A lesson, one might say in not seeing the forest for the trees, losing the big picture by focusing too tightly on one block of time. Something to keep in mind as our interest trends toward focusing on and isolating items, issues, and individuals.

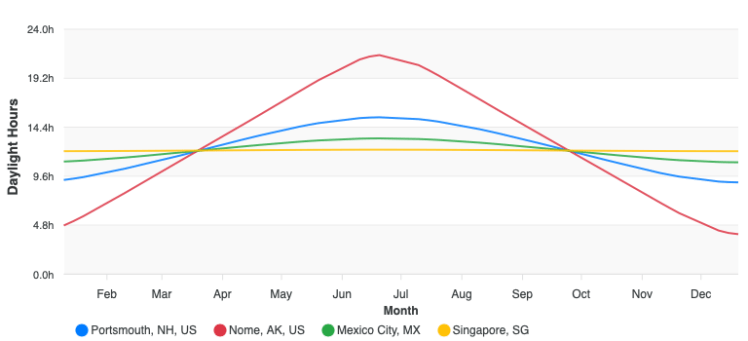

It’s also true that your view of and perspective on this point of inflection likely varies based on where you reside. We are kind of in a sweet spot here in New England with daylight ranging from about 9 to 15.5 hours across the year.

A colleague in Nome, Alaska would be looking at a range from approximately 4 to 21 hours, while one in Mexico City would only experience only a 2-hour shift. And what of our friends living in Singapore, Bogatá, Nairobi, Pontianak, or Quito. I’m betting that not even the geekiest of quants living in one of those cities on the equator would spend even one of the 365 days in the year thinking about hours of daylight. For as we know, interest, information, insight, and beauty come from variation.

A More Human Inflection

The solstice also represents a more figurative point of inflection. For those of us who celebrate, Christmas season is a time when so many of our routines get turned upside down. Everything from the music we listen to, the amount of online shopping we do, the food we eat, the trees in our living rooms, decorations in our yards, the drinks we order at Starbucks, and the Hallmark movies we watch. Similar to the Northern Hemisphere figure cited at the top of this post, it’s about 90% of us in the USA who celebrate Christmas. Interestingly, a figure significantly higher than the percentage who identify as Christians, a phenomenon to keep not too far in the back of our mind as we increasingly consider culture in our work and daily lives.

Then there’s the proximity of the winter solstice to the end of the calendar year. It’s a time when we often look to turn things around, to flip things on their head. Ideally, our resolutions for the New Year would be the result of careful thought. Alas, all of the hustle and bustle cited above leaves us little time to think during the Christmas season, never mind time for serious reflection and introspection, which are interconnected but different. Perhaps that’s one reason why so many of those resolutions fail before we even begin to notice the increase in daylight.

And what of that calendar year itself.

As a self-described data geek, much of whose career in education has been devoted to creating and maintaining (with a bit of interpreting) scales and constructs that are at best arbitrary, often are capricious, and sometimes are not scales or constructs at all, I have always been fascinated by the year.

First, unlike so many of our scales and constructs, the year is a natural, physical, measurable, phenomenon. One trip around the sun. A little more than 365 days (a day is another natural phenomenon), a difference which we cleverly adjust for every four years. I’ll admit that I am a social scientist with scale envy.

Second, as demonstrated above through our daylight example, there are significant and interpretable indicators that vary regularly throughout the year. Indicators that inform policy and important actions such when to take that beach vacation or when avoid a trip to Baton Rouge (fyi: mid-August). There’s that scale envy rearing its ugly head again.

But the really fascinating part, to me at least, is that so much of the rest of the things that we routinely associate with the natural phenomenon known as a year are just as arbitrary as our test score scales.

A Year Is A Year Is A Year

We can begin, of course, with the notion of the 12-month, January 1 – December 31 calendar year itself. We know that our Gregorian Calendar is only one of many ways in which a year is divided and described. We are familiar with celebrations of the traditional Chinese calendar with its New Year and symbols – we are currently wrapping up the year of the snake. We know Rosh Hosannah and more recently more of us may have become aware of the Hijri New Year.

Although those years have different starting points and even lengths, each, I believe, is grounded in the cycles of the moon, some more so, some less. Lunar cycles are also a natural and observable phenomenon, but don’t line up neatly with our trip around the sun, leading to interesting decisions and variations.

And what of our calendar and this chaotic confluence of the solstice, Christmas, and the end/beginning of the year. Is it a coincidence that the three events are coincident? Of course not.

We’ve all heard the stories of the indirect link between Christmas and the winter solstice via popular pagan festivals associated with the date. But what of the new year? Even in the pre-revolutionary days of the US colonies the new year was celebrated in March – centuries after those rascally Romans shifted the new year to the beginning of January, their newly added month named in honor of Janus, the god of transitions, beginning, and endings, often depicted with two faces, one looking forward and one looking back – as we are wont to do at this time of year.

So, the dates of the new year and Christmas were related to, but not the same as, the winter solstice. Close enough for government work one might literally say. And that’s another important lesson for us to reflect on at this time of year, the concept of close enough.

We Used To Be Happy With Close Enough

Growing up (another way of saying back in the day), the seasons neatly began of the 21st of December, March, June, and September, respectively. Then at some point, we started referring to those dates as the “first full day of …” Now, we seem obsessed with knowing the exact minute that one season ends and the new one begins based on the location of the sun. Does it really matter? Personally, I’m fine with sticking with the 21st – and not only because it helps me remember my cousin’s birthday on the first day of spring.

Approximations serve us well.

I am OK with both of the approximations that we use for human pregnancies, 9 months or 40 weeks, even though they are internally inconsistent given that if you ask 10 people how many weeks there are in a month 9.5 out of 10 will say 4.

That a baseball or football game will last 3 hours.

That it will take 2 hours to drive to Boston during the day but 1 hour to drive home at night.

I am even OK with Macy’s 1-day sales that routinely run for 2-days plus a preview day, but that’s a different story.

I think that we should be happy with the approximations that are test scores on large-scale tests and the inferences that they support about student achievement. We should stop trying to refine those tests to provide more precise estimates. Those resources would be better used elsewhere. More precise estimates of students’ overall proficiency have as much added value as knowing that in the northern hemisphere spring 2026 begins on March 20th at 10:46 am EDT, which by the way would have been 9:46 am EST back in the day.

Which brings me back to the northern hemisphere and the celebration of Christmas in the USA, each comprising about 90% of their respective populations. It’s efficient to make decisions about calendars, vacations, sales at stores, etc. based on things that apply to 90% of people. And efficiency (much more than comparability) has long been the driving force in large-scale testing. And, on average, that’s been good. It’s not surprising, therefore, that at this point of inflection in large-scale testing as folks focus on integrating AI into the testing process, I see a lot of talk of increased efficiency.

But, in education, in general, and large-scale testing, in particular, we know firsthand the harm in valuing efficiency over validity.

What I would like to see use resolve in 2026 is to take the time necessary for reflection and introspection (as individuals and a field) on what we are gaining with increased efficiency. If it is not efficiency in support of enhancing validity, fairness, and equity, then we need to resolve to keep thinking.

That shouldn’t be too much to ask.

Good tidings to you and yours.

Best wishes for a joyful solstice, a Merry Christmas, a Happy New Year.

Take some time to rest, to refresh, and to reflect.

Header image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

You must be logged in to post a comment.