Earlier this fall, Andrew Ho made two posts on LinkedIn related to technical advisory committees; that is, those groups of experts convened periodically to advise state policymakers on the design, implementation, and operation of their state assessment programs. The first post was his TAC Bingo Card, which Andrew described as his “half-serious attempt to source his most frequent comments” at TAC meetings. The second post was related to the list of state TAC members that NCME compiled recently.

Thinking about the concept of “most frequent comments” while reading line-by-line through the names of current TAC members and pausing between the lines to remember some of the TAC giants no longer with us, a thought started to take shape in my mind:

Ours is a field steeped in oral tradition, with TAC members its primary storytellers.

Ironic perhaps for a field comprising academics who persevere or perish by the written (i.e., published) word, state policymakers adroit with memoranda and bureaucratic paperwork, and assessment contractors with furnaces fired, primed to produce voluminous technical documentation at the drop of a hat or push of a button.

Nevertheless, I submit that much of the critical information about educational measurement, assessment, and large-scale testing; that is, the history, beliefs, ideas, and culture of our field is transmitted through oral communication.

An Oral Tradition

For those entering the field, that communication occurs between professors and graduate students in university settings. The lecture, despite all its shortcomings, remains a powerful tool for conveying information as well as sparking interest and ideas. For sure, there are readings, but the true value of a carefully curated collection of readings has always been the discussions they spur.

As we move through our careers, conferences are the primary vehicle through which we share information with colleagues. On paper there are papers, but at least in our field the reality (and expectation) is that the primary form of communication at conferences is verbal. Whether during sessions, between sessions, at formal receptions, or in informal gatherings over drinks in the evening, we are most receptive to information transmitted by word of mouth. At the Center for Assessment, my favorite activity was the annual Colloquium, two days each spring dedicated to extended conversations with experts in emerging areas, little of which was captured in writing.

And for sharing critical information outside of our bubble, communication with and through state policymakers, we have technical advisory committees, TACs. A typical two-day meeting can yield a wealth of information dealing with not only the what and the how of state testing, but also the who, where, when, and why we have done things in the past, currently do things, and may consider doing things in the future. Almost all of that information communicated verbally.

The bulk of written communication transmitted during TAC meetings is unidirectional – from the state to the TAC. Andrew’s pithy briefs notwithstanding, virtually all of the information conveyed by the TAC to the state is done verbally during the TAC meeting.

Telling Our Story

The topics included on Andrew’s Bingo card compilation of most frequent comments are not frequent because he is on a lot of TACs or likes to repeat himself. They are frequent because they address core concepts that bear repeating, stories that must be told time and time again.

Throughout my career, I interacted with TACs in a variety of roles: assessment contractor, state department staff, consultant, TAC member, TAC facilitator, and indirectly as a TAC tutor – advising psychometric staff on how to interact with TAC members. As I reflect on my experiences across those roles and years of TAC meetings, the importance of our oral tradition is crystal clear.

In the beginning, I listened attentively to state testing icons like Dale Carlson, Doug Rindone, Roger Trent, Steve Ferrara, and Mitch Chester to name just a few. Their lived experiences helped shape my actions and are relevant to the current generation of state assessment directors; but they are largely lessons that must be passed from generation to generation through TAC meetings.

And all of those TAC advisors. As a TAC facilitator, I felt that it was my job to allow them to tell the story the state and/or contractor needed to hear. Drawing on my music background, I viewed myself as a conductor tasked with knowing how and when to bring in and bring out each voice to maximize its impact while crafting the overall story for the state. Understanding what each TAC member had to contribute, counting on Laurie Wise to start the discussion by getting to the heart of the issue, knowing when to turn to George Madaus to remind us of validity or assessment history, allowing Ron Hambleton the time he needed to work through an elegant solution, and sensing when it was time to look to Barbara Plake for a much-needed reality check. Knowing when the meeting needed the precision of a classical concerto and when it had to flow like a jazz jam session was my responsibility. In my last facilitator gig in Louisiana, those voices to be mixed included Karla Egan, Ellen Forte, Pete Goldschmidt, and Greg Cizek accompanied by some senior staff from DRC. Different voices, a few different issues, but the same process, the same oral tradition. I am sure that TAC facilitators today count on Andrew making one or more of those most frequent comments exactly when it is needed most.

For better or worse, written documentation of TAC meetings is rare. There are TAC minutes, of course, action items, and some TACs have records of formal votes; but so much of the information conveyed via TAC meetings is not captured formally or for posterity (or for the next assessment contractor or new assessment director).

As NECAP gave way to PARCC and Smarter Balanced in 2013-2014, we did task Bill Erpenbach with documenting the 10-year history of the program through its TAC meetings. As always, he did a thorough and masterful job. Alas, for any number of reasons that project did not make it through to dissemination.

Words and Music

I am not suggesting, of course, that all critical information in our field is passed only via the spoken word.

I was thrilled when one of my students this semester drew critical information from an old article by Sue Rigney on the assessment of students with disabilities, but what I remember most and have done my best to communicate through the years is the wisdom shared by Sue during her presentations at CCSSO meetings, lunchtime conversations, and afternoon walks after a long day of sessions at the large-scale assessment conference – key advice on how best to deal with USED on various matters, where there was flexibility, where the wasn’t, and where there might be flexibility if handled carefully and cautiously.

Another student devoured Greg Cizek’s 1999 book, Cheating on Tests: How to Do It, Detect It, and Prevent It. But the class also learned a lot about cheating and the realities inherent in detecting and dealing with it from my stories of the experiences Greg and I shared in 2019 as members of Louisiana’s Test Irregularity Review Committee.

Personally, for years early in my career, I always carried a copy of Popham’s Criterion-Referenced Measurement (1978) with me and even today a dog-eared copy of his Transformative Assessment (2008) sits on my desk. Not to mention the countless other books he wrote. However, it was not his books, but rather a series of conversations with Jim, organized by Marianne Perie for the Large-Scale Assessment SIG in the early years of NCLB that solidified my understanding of the relationship between standards, assessment, and accountability and shaped the messages that I have shared at TAC meetings for the past 20 years.

Oral tradition.

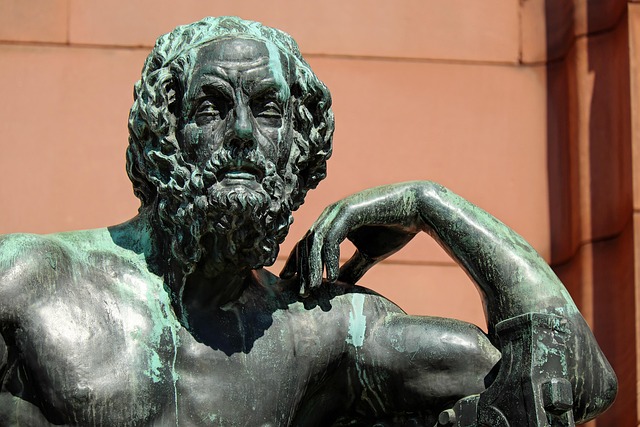

We are long past the time of Homer when oral communication was ephemeral and needed to be repeated lest it be lost forever. But we would be naïve to think that the mere existence of video and audio recordings means that the need for storytellers and TAC members to pass on the concepts and culture of the field has passed. Just as many of the books I am pruning from my professional library sadly are in mint condition, I’m sure that many videos and podcasts containing valuable information will sit idle awaiting a storyteller to herald them or to include them in a Bingo card distributed via LinkedIn.