As a group, educated and educators, we love books. We believe and embrace the words of Toni Morrison: Books are a form of political action. Books are knowledge. Books are reflection. Books change your mind.

Personally, I cannot imagine life without books. Whether in my office writing, in the family room, dining room, kitchen, or even when working out in the basement, I spend my days surrounded by books.

It was with sadness and dismay, therefore, that I read the following sentence:

“In American high schools, the age of the book may be fading.”

With those words so begins Dana Goldstein’s New York Times article on the sad state of students reading whole books. Although the phrase “may be fading” suggests uncertainty that offers a glimmer of hope, the message conveyed in the remainder of the article is summed up nicely by its headline, “Kids Rarely Read Whole Books Anymore. Even in English Class.” And although this article is focused on high schools, a quick online search or AI query reveals that the issue extends in both directions, down to middle school and up to college. Many kids are asked to read no more than one or two books per year.

The article contained a laundry list of possible factors contributing to the lack of book reading. Some of those factors were focused on the students themselves:

- The rise of social media and other platforms competing for students’ time and attention resulting in less interest in books.

- Along with the effects of such technology on students’ “stamina for reading.”

The bulk of the factors cited, however, were external to the students and included the familiar culprits: standardized tests, the Common Core, [greedy] curriculum publishers, money, politics, and of course, the pandemic.

As I read through the list, I found myself thinking less about how much each of the factors discussed might contribute to “the problem” and more about how the sheer number of factors and the complex interactions among them must be creating chaos in the classroom.

Let’s start with standardized tests, always a good place to start when complaining about the state of public education. Curriculum and Instruction (the other two legs of the C-I-A stool) eschew whole books in favor of short excerpts in response to “significant pressure” to be aligned with the content of standardized tests used for accountability and other high-stakes purposes. In other words, test prep. The focus on excerpts, in turn, is then cited as a leading cause of the decade-long drop in reading scores on tests such as NAEP – decades long if you live here in Maine. Big Brother and his standardized tests, apparently, have contributed to a classic “2 + 2 = 5” dystopia in public education.

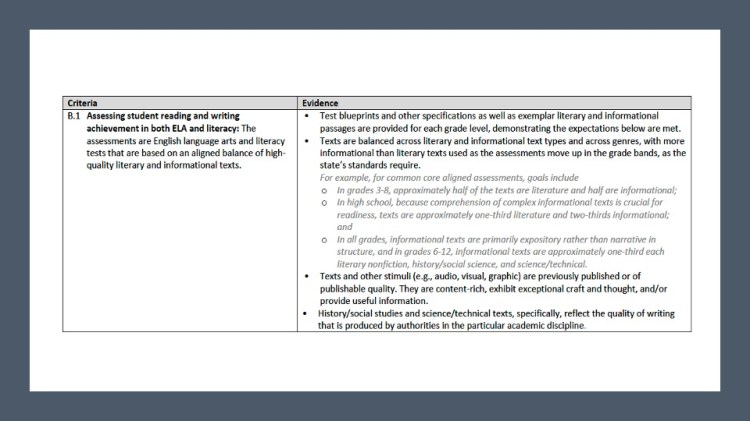

If those college-and-career-readiness tests themselves are not to blame, attention shifts to the standards to which they are aligned; that is, the Common Core State Standards or the name by which that rose is currently called in your state. Recall that the CCSS called for an increased emphasis on informational texts. In the zero-sum game that is the high school curriculum, an increase in informational texts means a decrease in literary texts (i.e., books).

If the CCSS were too subtle for you, recall the CCSSO criteria for the procurement of high-quality assessments:

In 2026 we cannot leave politics out of the blame pie we are creating – and in the spirit of America 250 let’s make sure it’s an apple pie. With regard to books, the arguments suggest that villains exist on both sides of the political spectrum. Conservatives are making it impossible to assign whole books because of the growing list of themes that cannot be discussed in school. Liberals are making it impossible to assign whole books because of the demand to move beyond the “stagnant list of classics” written by dead white guys (see also cultural relevance, engagement, etc.). In its simplest form, adding more authors and texts to a fixed school year means shorter excerpts rather than whole books. Again, it’s a zero-sum game.

And the pandemic. Kids out of school had more time to read than ever before but we lacked the infrastructure to ensure the equitable access to books that the classroom provides. A COVID Catch-22.

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

The problem is that each of the arguments made above is to some extent true and to some extent false.

Standardized tests don’t have to (and probably shouldn’t) lead to test prep, but they do. Neither the CCSS nor the CCSSO criteria prevented schools from assigning whole books or kids from reading them, but they likely did both.

The same social media platforms that erode kids (and adults) stamina for and interest in reading whole books can create bestsellers overnight – and do so on a regular basis. I can attest that whether people read those books that they purchase is a separate question altogether, but let’s save that issue for another post.

And the inconvenient truth is that beyond tests, standards, and stamina, we are also asking educators to figure out how reading books (whole books or excerpts) can best be used to support the changing and increasingly complex skills being asked of teachers and students, whether you refer to them as 21st century skills, soft skills, noncognitive skills, durable skills, or by some other name.

Tests, standards, social media, durable skills, advanced technology, voices from the left of them, voices from the right of them that volley and thunder. We should not be surprised that educators, like so many Hamlets are paralyzed by indecision.

Reading Between The Lines

The devil, as he always has, lives in the details. If we decide that it is important for kids to experience more books from beginning to end, to what extent does it matter whether that experience is through the written word, an audiobook, a video, or perhaps some other multimedia immersive experience?

If we decide that reading written words is key, does it make a difference whether that experience is online or with a physical printed book? Is one more important than the other? Can students choose? Do they need to be proficient in both?

The article that spurred this blog post appeared in the online version of the New York Times on December 12th. If you access that article today, you will find the following note:

A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 15, 2025, Section A, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Students Are Getting a Reader’s Digest of Books.

The change in headline suggests, that at a minimum, the NYT acknowledges that they are reaching different audiences with their digital and print versions; the audience for the print version undoubtedly older and more likely to get the reference to Reader’s Digest versions of books. That same older audience might also be more likely to get the reference in the title of this post.

But not everyone familiar with the story actually read the NYT article.

A portion of that older demographic may have accessed the content of the story through a news report on television or the radio.

An even larger portion of the young’uns who access information online came across a post, read the headline and maybe the brief summary, but never clicked on the article.

Regardless, we all came away from our experience with the shared and common information that kids are being assigned and are reading fewer whole books from beginning to end, and the implication that this development is bad.

We want the solution to be straightforward. Now that we have identified the problem, let’s fix it. Get kids more access to books. I want to be able to end this post with the simple advice: Book ‘em, Danno!

But we know that it’s not that simple. What we do next is still up in the air. The future of books and their role in the curriculum is not written yet.

On the one hand, that uncertainty offers endless possibilities.

On the other hand, I hate it when a story ends with a cliffhanger.

To be continued…

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

You must be logged in to post a comment.