“The American education system fails the students who need it the most.”

WTAF

That was my reaction as I read the opening sentence from the request for information (RFI) on school-level academic growth indicators issued by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP).

HELP! Indeed. Help me understand what’s going on here.

Like many, I believe that considering growth as well as status is fundamental to understanding and describing the achievement of students within a school. Therefore, the fact that the committee was interested in learning more about school-level academic growth indicators seemed like good news. And that’s the way I saw my colleagues interpreting the RFI on LinkedIn and other platforms. But then I read the document.

Although some may view the committee’s interest in growth as a positive step forward, the tone set by the opening sentence of the RFI takes us two decades back.

Back to the talk of failing schools that accompanied the initial rollout of NCLB by George W. Bush and back to the Obama/Duncan honesty gap. Yes, despite the great political divide, this blame public education, blame the schools, blame the teachers rhetoric has been bipartisan from the jump.

We’ve careened down this road before and found that it’s a dead end with a reinforced concrete wall. Continuing to bang our heads against that wall gets us nothing but a concussion. As Einstein most likely didn’t say,

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”

And as Jim Popham did warn us repeatedly, there is very little that you can infer about the quality or effectiveness of a school simply on the basis of a test score. That admonition holds whether that test score is transformed into a status indicator such as an achievement level, subtracted from another test score to compute a gain score, or ultra-processed into an actual school-level academic growth indicator.

That’s not to say that status and growth-scores based on state test scores are not valuable. Their value may be limited, but sometimes it’s important to know a person is too small (or too large) to go on the ride. That’s the level of information that we can and should expect from a state test.

If we want to better understand why the child is too small (or large) for the ride this year or whether it’s likely that they will be able to go on the ride next year, we need additional information – information beyond their current height.

The same is true of school effectiveness and school quality.

If we want to know more to understand and explain student status and/or growth, we need to dig deeper, beyond test scores. No matter how much “better” we make those tests.

Improving the quality of state tests might improve the accuracy and/or precision of that information, but it won’t erase its limitations. If we want to make inferences about the effectiveness of a school, we need more than a test score.

Informing Parents

As Wendy Yen famously noted, parents want information about their child’s status and growth. What can they do now? How does that compare to what they could do last year? And also, is that good enough?

What can/should that information look like today? Most definitely, not scores.

Parents need clear, solid content- or skills-based descriptions (and ideally examples) of what their child can do (status); and to provide initial context, similar information about what the child could do at the beginning of this year or the end of last year. (This is neither the time nor the place to dive into the esoteric discussion about whether that change in performance is gain or growth.)

In addition, parents need interpretations about that performance, about whether it is “good enough” relative to state standards, expectations, and the child’s plans for the future. It’s likely that some of that information will be criterion-referenced and some of it will be norm-referenced.

Informing Policymakers

Policymakers need much of the same information, albeit at aggregate levels, but they also need more, much more. Policymakers need information that will help them answer the “why” questions. They need contextual information about student demographics, school conditions, and other factors that are related to student achievement such as absenteeism, mobility, school safety and climate, etc. Information about what those factors look like now, how they have changed, and how they are likely to change moving forward. They need information about the success (or lack thereof) of specific programs that have been implemented in an attempt to improve student performance; that is, they need information from well-designed and implemented program evaluations.

To make “policy” without such information is simply tossing darts while wearing a blindfold. Somebody’s going to get hurt.

Failing The Students Who Need The Most

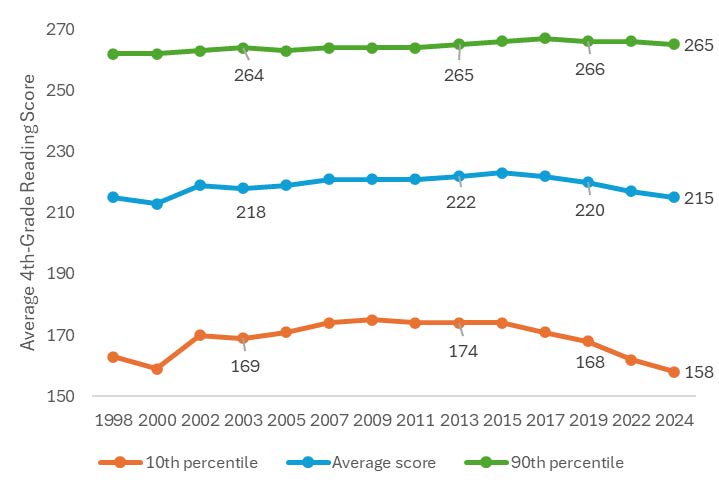

A graphic like the NAEP results depicted above, cited at the beginning of the RFI, is disconcerting, or even alarming, and is a clear indicator that there is a problem to be solved. What it is not, however, is evidence that the American education system is failing the students who needs it most.

If we are taking the time and want to provide useful information to the HELP committee and other policymakers, our first and most important task is to help them understand that fact.

Image by Bishnu Sarangi from Pixabay

You must be logged in to post a comment.